Review: Dancers of the Nightway

by Ivy Vance

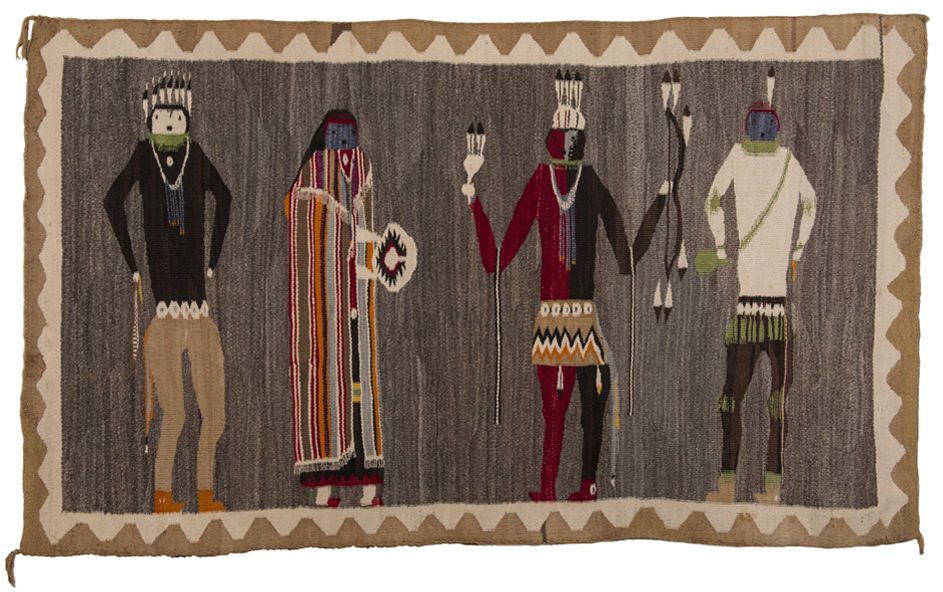

The current exhibition at Mount Holyoke Art Museum Dancers of the Nightway displays a selection of Navajo weavings from the collection of Rebecca and Jean-Paul Valette. For this unique exhibition the collectors also acted as the curators and chose the pieces as well as the thematic content. These large, colorful textiles currently cover the walls and floors of the main gallery depicting the sacred figures that participate in the Navajo Nightway ceremony. The weavings are exceptionally beautiful; the use of color and form combined with the craftsmanship and their immense size produce lasting impressions on the viewer. Although visually striking, for this student, the provenance and creation of these textiles provokes more interesting questions than the exhibition itself.

The weavings in this exhibition are not the abstract, geometric textiles that are usually associated with the Navajo Nation. These works make up a lesser known class of Navajo textiles that depict Navajo deities. Specifically, the weavings in this exhibition portray the Yeibichai dance, the conclusion of the Nightway ceremony, a healing ritual performed annually by members of the Navajo community. Traditionally, the images of these deities were made only in sand paintings, which would be later be destroyed; lasting images of their gods were not supposed to be produced. In fact, these figural weavings only exist because of pressures from the growing market to create commercial objects, fed by settlers of the American Southwest. Unlike the geometric weavings, which were used by both the settlers and the Navajo community, these pictorial textiles were created solely to feed the demand of a burgeoning market that called for the inclusion of Navajo deities. Immediately questions of authenticity, ownership, and ethics are called into question. However, the exhibition is not framed around these provocative questions. Instead, the textiles are presented as an ethnography of the Nightway ceremony. The wall texts and supplementary objects focus on process, meaning, and the specifics of the ceremony. I feel that this approach takes away the potency of these multilayered objects.

In the lobby, there is a small exhibition curated by contemporary Navajo weaver, Lynda Teller Pete. In the text next to the textile, Yei Weaving with Figures, Pete describes the hardships many Navajo weavers faced at the turn of century. For some, meeting the demands of the market was the only way they could provide for their families. Many of the people who partook in this practice felt conflicted about weaving these sacred figures into fabric that was to be bought and sold. Although this text is how the museumgoer is introduced to this practice of weaving, it is separate from the rest of the exhibition. Is there a way that this critical stance could have been part of the exhibition as a whole? Rather than meticulously reciting each of the deities’ names and the symbolic content in each weaving, there should be more attention paid to the dual nature of these textiles: as sacred and commercial, as betrayal and relief, as authentic and inauthentic. Through acknowledging and measuring these dualities through interviews with Navajo people or textural analysis the textiles could be assessed beyond their ethnographic history and be understood as complex, aesthetic objects.

Dancers of the Nightway: Ceremonial Imagery in Navajo Weaving is on view at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum through May 29, 2016. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/artmuseum/

Ivy Vance 13F is a Research Assistant at the Institute for Curatorial Practice.

This post is part of a series of essays, opinions, and reviews written by students, faculty, and staff of the Institute for Curatorial Practice.