By Lexx Cespedes

Lexx Cespedes 16F is a recent Hampshire College alumn whose Division III focusing on Labor Studies, U.S. History, and Children’s Literature. Here, they share their community-engaged research methods and reflections on creating an original children’s literature series focused on union families, children’s nuanced understandings of labor, and recent histories of organizing in the Northeast. Lexx was a recipient of the 2019 Common Good Summer Social Justice Grant and 2020 Common Good Scholar Project Grant.

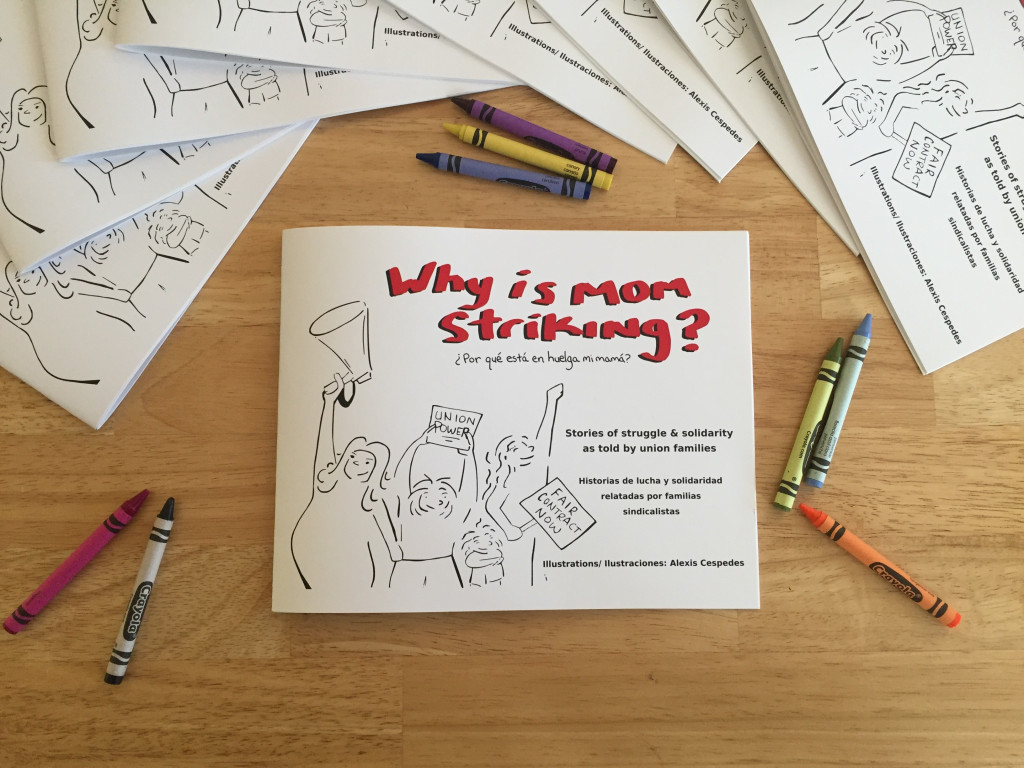

Over the summer of 2019, I collaborated with parents and children in local trade unions on the first edition of a storybook series titled Why Is Mom Striking? I was interested in exploring depictions of class struggle in storybooks, on a quest for children’s literature that stimulates conversations about the value of rank-and-file work. The first publication of illustrated conversations with participant families was released in September 2019.

I’ve been involved in solidarity work with the local labor movement since I moved to Western Massachusetts four years ago. While my organizing and educational experience deeply informed this project, it’s impossible to separate Why Is Mom Striking? from my own material experiences. I was deeply politicized by the economic obstacles my family faced. As a young person, I observed the injustices my parents and younger sister faced at work, toiling day-to-day to barely make rent and keep the lights on, experiencing workplace abuse, and attempting to make ends meet with a wage only conducive to surviving. I’ve had similar experiences in every job I’ve had since I became a working age.

In my own life, I noticed that there was a deficit in children’s literature that positively and honestly portrayed working-class people. Where were the books that portrayed people like my mom working double-time to feed her children before she nourished others waitressing? And stories of women like her, challenging injustice on the shop-floor as well as at home? When I began this project, I researched existing literature depicting workers, working families, and particularly, strike actions. Children’s librarians would scratch their heads with me every time I asked where to find books that incorporated labor historical records and workers engaged in class conflict. The existing literature was, indeed, slim.

The texts I did find greatly inspired my approach. There were key projects that I looked towards as examples of activating rank-and-file workers’ experiences with visual storytelling. Projects such as ¡Sí, Se Puede! / Yes, We Can!, written by Diana Cohn and illustrated by Francisco Delgado, exemplify the power of children’s storybooks as political education. A story about the Justice for Janitors strike in 2000, the book centers young Carlitos fighting alongside his mom for better working conditions. The story also highlights the intersections of immigrant justice movements and labor justice through historical fiction. The webcomic series El viaje más caro / The Most Costly Journey, a partnership between the Vermont Folklife Center, Open Door Clinic, UVM Extension Bridges to Health, UVM Anthropology, and Marek Bennett’s Comics Workshop, depicts Latin American migrant farmworkers’ experiences in Vermont’s dairy economy. The project centers workers’ lived experiences while providing bilingual resources for mental health outreach initiatives, using collaborative arts for labor and health advocacy. Each of these projects is an exercise in representing the experiences of workers at the margins in the United States, presented as a powerful tool using arts education and visual storytelling.

Why Is Mom Striking? embodies my encounters on the shop floor as well as many other working people. It is a political education project that not only engages children with working-class history but centers them as narrators within the contemporary labor movement.

Solidarity Organizing in the Pioneer Valley

The two years leading up to Why Is Mom Striking?, I began working closely with dining workers in Local 164 of UNITE HERE! New England Joint Board, representing Hampshire College’s dining employees. At the start of 2019, the College underwent a significant financial crisis that resulted in a series of measures to balance budgetary requirements and maintain federal accreditation. One of the measures taken by upper administration was to dissolve a pre-existing dining contract with Bon Appetit Management Company, thus, eliminating jobs for 34 food service workers in our dining hall. The manoeuver jeopardized the very existence of Local 164 and many hard-fought protections by union members since their contract was won by a supermajority in 2014.

Dining staff’s unionization was one of the most successful and passionately fought for campaigns in the College’s history. It was bolstered by a large contingent of students working in solidarity with dining staff, culminating in a sit-in at the college Treasurer’s office in 2015. The unionization effort of dining staff was not just passionate and driven in a symbolic sense, but a material win for economic justice on our campus. In their first contract, dining workers bargained for an increase to $15 minimum wage, long before the State of Massachusetts initiated an incrementalist minimum, thus forcing Hampshire College to raise the minimum wage to $15 for all campus workers. The campaign demonstrated the radical necessity of grappling with the ethics of undervaluing the food service workers who nourished the community for decades.

Before the events of Spring 2019, Local 164 was the only union on campus representing rank-and-file employees. The decision to lay off all dining workers led to the union’s dissolution, and the lowest-paid workers at the College were given only three months notice before their benefits would end. The decisions made by the college in the face of financial challenge left the entire labor force in precarity, but as is always the case, the most marginalized were affected acutely. Years of cost-cutting and unfair labor practices have been battles rank-and-file workers have historically fought at Hampshire College and universities throughout the United States. Throughout the project, I organized alongside Local 164 members on a hardship fund supporting laid-off employees and their families, coordinated a community benefit concert to stand in solidarity with the union, and advocated endlessly to publicize the effects of unfair labor practices on working families at our College.

The Strike-wave at Home

My experiences organizing with Local 164 were incredibly politicizing, as were many other solidarity actions that I participated in while working on this project. In April 2019, 31,000 Stop & Shop workers went on strike. Their union, United Food & Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) authorized the action at over 240 stores throughout the Northeast. After the previous 3-year contract with UFCW expired, Stop & Shop’s parent company, Ahold Delhaize, proposed increased healthcare premiums and deductibles, reduced retirement plans, and loss of premium pay for new associates. The stipulations in the newly proposed contracts with Ahold Delhaize raised alarm among workers, leading the five locals of UFCW representing Stop & Shop employees to strike in early April. The stoppage resulted in a $110 million profit loss for the company and a 75% drop in customers by the second week of the strike.

The 10-day stoppage was an incredible example of the current strike wave rippling across the United States. Stores rapidly became deserted. In less than a week, the company frantically turned to scabs, or paid strike-breakers, to deal with rotting produce and empty register counters. The largest private sector strike in years resoundingly made its mark on local, coalition organizing; a decreased customer-base by the second week of the strike reflected an outpouring of community support and donations, a hardship fund for employees lost wages, and solidarity from other trade unions such as Boston-based Local 25 of the Teamsters. In a letter from the local’s president Sean O’Brian, the union representing 700 Stop & Shop warehouse employees vowed to respect the picket line leading up to UFCW’s strike authorization. Stop & Shop strikers turned away distributors’ trucks to disrupt the supply chain, bolstered by endorsements like Local 25’s. The action was near its close by Easter day and many Stop & Shop parents celebrated the holiday with their children on the picket line.

While I illustrated the first book, I participated in two other local labor actions that demonstrated similar force. In Greenfield, Massachusetts, U.E. Local 274 workers at a Kennametal Inc. manufacturing facility participated in a 3-day strike to settle contract negotiations with the company. In a climactic moment, I witnessed paid strikebreakers being escorted into the facility protected by Greenfield Police. Strikers booed in protest and rallied around the cars entering the gates. The line sang “they say in Franklin county, there are no mutuals there” to the tune of American folk classic “Which Side Are You On?” sung with acoustic accompaniment on the picket line, and this still resonates with me.

The Northampton Association of School Employees, engaged in their battle to close a significant wage gap, established work-to-rule after a series of bad faith contract proposals with the school district. I also participated in multiple stand-outs alongside community members advocating for NASE.

In both the Stop & Shop and Kennametal actions, workers had not initiated a strike since the 1980s. In Northampton, NASE not only mobilized a popular base of community members, but energized their rank-and-file membership by setting a precedent for open bargaining, or open-door meetings over contract proposals between management and employees. In each of these instances, children participated in rallies, walk-outs, and socials in solidarity with striking workers.

The Process

After years of organizing in the local labor movement, the conversations I had with working parents and children often led to a similar question. Where was a book that families could read together to see themselves represented in stories about their labor struggles? In the interview-based process of creating Why is Mom Striking, I used drawing as a narrative storytelling aid and facilitated questions between children and parents about their labor activism in developing material. The recorded interviews provided the base for each story in a language that would be accessible to child readers’ because the narrators of stories were themselves children or parents of children. The only exception to this method is interviews with expectant parents, who were given prompts about how they would engage their children with work and workers’ in the future, how parenthood could affect their participation in organized labor, and lessons they would share with their children. The ultimate trajectory of the series is to produce an inter-generational arc where union grandparents, parents, children, grandchildren, and soon-to-be parents could share their stories to stimulate conversations about rank-and-file work.

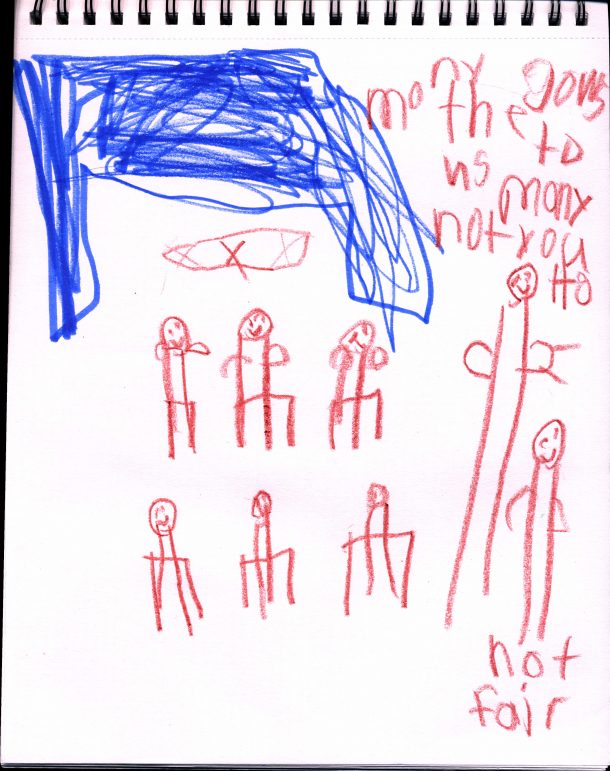

In one interview, young Alex used drawings to talk about the fight for fair wages with the Massachusetts Teachers’ Association, a union representing 110,000 school employees throughout the state. Alex considers himself both a union member of his mom’s union, the Communication Workers’ of America, as well as the M.T.A. He describes himself as an avid labor organizer, citing his experiences on the picket line with Stop and Shop workers as well as teachers at Fund Our Future rallies. He talks about how he organizes meetings with the help of his mom, Alicia. In his drawings, he shows that when bosses withhold fair wages, students and teachers suffer the most, hence the declaration: “money goes to us, not to you— not fair!” Alicia is currently a lead organizer at Jobs with Justice and a member of the C.W.A, a union that in recent memory authorized a walk-out of 20,000 AT&T workers throughout the Southeast in August 2019.

Alex insists that when workers organize together, they win against bosses who withhold money from the very people who make wealth for their employers. He explained that when white bosses and doctors deny black workers ‘…medical health…,” or healthcare coverage, those very workers can organize collectively to oust racist management. In another instance, Alex also said that Stop & Shop cashiers replaced by Marty, an anthropomorphized cleaning detection bot, can also protest labor-saving technologies that replace real working people. Perhaps a defining moment in our conversation was when Alex made his connections between the Stop & Shop workers’ actions and the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Montgomery Bus Boycotts and the Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968.

I was moved by Alex’s reminder of how Martin Luther King Jr. ‘s work for economic justice intersected with his leadership during the Civil Rights movement. The Memphis Sanitation Strike of 1968 was the last action King participated in before his assassination. The same year, he and S.C.L.C. launched the Poor People’s Campaign, a cross-coalition movement calling for urgent amelioration of poverty, homelessness, and scarcity among the American working class but particularly redistribution of wealth for black workers. The campaign called for militant non-violent strategy, culminating in a general strike that would halt government and industry until conditions to end poverty were met. In a meeting with at American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (A.F.S.C.M.E.) members at Bishop Charles Mason Temple in Memphis, notably remembered as his “All labor has dignity” speech, King emphasized the importance of not only seeing work but organizing to restructure systems in favor of working people:

Now the problem is not only unemployment. Do you know that most of the poor people in our country are working every day? (Applause) And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation. (That’s right) These are facts which must be seen, and it is criminal to have people working on a full-time basis and a full-time job getting part-time income. (Applause) You are here tonight to demand that Memphis will do something about the conditions that our brothers face as they work day in and day out for the well-being of the total community. You are here to demand that Memphis will see the poor.

This project has given me a new appreciation for children’s ability to synthesize working-class history with material observations of work and workers in their lives. Alex’s storytelling also reflected his observations of economic and political relationships, demonstrating both visually and in his narrative storytelling, that a power imbalance exists that is contingent on workers making value and employers profiting from wealth-creation. He also demonstrates a relationship between race, economics, and power by highlighting the struggles of black workers fighting for anti-racism in the workplace, historically highlighting the union as a vehicle for forceful change. We can understand his observations like so: educators are workers, they reproduce knowledge systems. Stop & Shop employees are as well, they do productive work. Historically marginalized workers follow the tradition of those in Memphis who fought against white supremacy and its relationship to economic power, replicated on the shop floor at the expense of black sanitation workers. Withholding labor and exercising collective power, Alex notes, disrupts o systems of authority. This is observed in action (a literal strike action) as well as taught as a value system from Alex’s formative curiosities with history, his mother’s labor activism, his social reality.

Final Reflections

In between vigorously doodling horrible bosses and working full-time, I embarked on a mission to illustrate a children’s storybook from and about union families. Each story’s theme ranges from standing up for fair workplace conditions to candid discussions about how we see work. The project is meant to highlight intersections of labor with movements of gender, class, racial, and disability justice, as well as international workers solidarity. Each illustration is rooted in the material experiences of its narrators: kids, parents, grandparents, and parents soon-to-be. I am excited to present each story from Aliza, Alex, and Alicia not only through color-able illustrations but in both Spanish and English for language accessibility. This component would not have been possible without the support of local artist Youme Nguyen Li with the Somos Todos Lideres and Panta Rhea Foundation as well as Melody Gonzalez of Guani Tanoli Translating and Interpretation. To find out more, and access downloadable pages for organizations, check out: whyismomstriking.wordpress.com.