Utopias are non-fictional even though they are also non-existent.

-Frederic Jameson (2004) 1

Utopia is an imagined concept of an idealized space. Directly translated from its Greek derivative, it means “no place.” Long before a utopia comes into fruition, it lives in an intangible world, occupying the place of the imagination. Portraying an image of the best life possible, it soon becomes apparent that a utopia cannot be emulated in real life. The concept dangles before us always present yet forever unattainable. Some ideals transfer to reality, but, as nothing is perfect, neither are these illusory places. Seemingly capable of inhabiting nowhere and somewhere at the same time, this dichotomy forces us to question how we think about these depictions of space.

Can a utopia or dystopia exist through the medium of art? How can we relate to a place if we have never experienced it? Is utopia merely an impractical dream that should just be abandoned? Various artists in this exhibition have used visual imagery embodying utopic and/or dystopic ideas to illustrate places that we cannot reach.

In the story Utopia from 1516, Thomas More wrote that a utopia is “an apocalyptic vision of the best earthly state possible.”2 This could not better demonstrate how utopia and dystopia are so heavily intertwined with and reliant upon each other. This combination is also evident in the works included in HIDDEN TRUTHS: DISRUPTING UTOPIA. While typically the themes of utopia revolve around solving issues of over-population, sickness, pollution, technology, and politics, there also is a realm of purely conceptual investigations, a place where mundane reality intersects with fantasy.

Ferns

1980

Cibachrome color photograph, 5/20

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst

In her photograph Ferns (1980), Sandy Skoglund propels us into a habitat plagued by repetition. It is a real place in the sense that a few elements are recognizable such as the room, table, chairs, and lamp, but uncomfortably so. The same woman fills the frame three times, appearing to be doing typical activities any person might do in their home, like eating or looking out the window. What makes the scenario so off-putting is the fact that her environment mirrors that of a solitary confinement chamber. She is alone and that is emphasized by her repeated appearance. She gazes out a fake window that is completely boarded up. She sits at the table with a plate in front of her and silverware in her hands, but there is no food. Detached from actuality, artificiality takes hold. Does she live in a world in which all nature has been destroyed and life only exists in interior spaces? In essence, this woman harks back to the post-war era housewife. She engages in an idealized lifestyle, in which everything is supposed to be perfect and have a certain order. She no longer needs to work, which supposedly frees up her time, but instead she is imprisoned by her home life. The world outside the walls of her home is just not there—as evidenced by the lack of a window view. She is forever in a limbo, trapped in a warped environment.

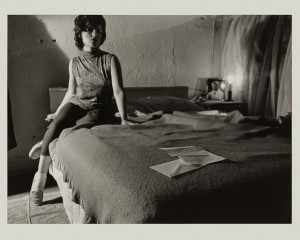

Untitled Film Still #33

1977

Gelatin silver print photograph; 7/10

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Photography plays a vital role in this distorted reality. It is the only medium that can effectively capture aspects of real life, but simultaneously expose a realm that cannot exist outside that of the photograph. Photography is much like utopia in this sense, as utopia flourishes best in the mind of its creator and dissolves into a dystopia once it takes a breath of air. Photography is a medium that evades us. In Roland Barthes’s seminal text Camera Lucida, he found that “What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph repeats what could never be repeated existentially.”3 Like Skoglund, Cindy Sherman plays with this idea in photographs such as Untitled Film Still #33 (1977). Sherman fabricates the story of the subject and limits it to inhabiting the frame of the camera. Sherman constructs spaces, forming images that appear to be candid, but are entirely fictional as she uses herself as a subject to briefly play out an invented life. We are deceived into thinking that what we see is authentic.

Artworks are alive in that they speak in a fashion that is denied to natural objects and the subjects who make them. They speak by virtue of the communication of everything particular in them. Thus they come into contrast with the arbitrariness of what simply exists.

-Theodor Adorno (1970) 4

Lurid Sky

1929

Oil on canvas

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Gift of Mrs. John Lee Bunce (Eleanor Howland, Class of 1926)

Art, especially art with utopic themes, seems to threaten the importance of real life. This is a very valid concern and encourages one to wonder whether or not art enhances or rather diminishes the only world in which we can participate. As Adorno concluded, what we know to be real is quite arbitrary in comparison to the limitless imagination. Do we yearn for a utopia just because reality is too boring? While Sherman tricks us into believing in the world in which we inhabit, Yves Tanguy pushes the boundaries and propels us into a fictional narrative that eradicates any room in which to place ourselves within the landscape. Surrealistic in style, Lurid Sky (1929) situates the viewer in a fantastical and preposterous dreamscape. An ominous yellow sky lingers above as biomorphic forms float about. The environment Tanguy crafted is nothing short of a bad dream. With no readily recognizable features, this imagined place transcends reality, exemplifying both utopic feelings of freedom of flight, but also a dystopic vision, with nowhere to land.

While utopias are often an attempt to devise a promising future in hope of a better tomorrow, they are mostly misleading; they force us to question everything we have become familiar with to the point that we are satisfied with nothing. It is a tragic truth that we can only hope to resolve, even though a conclusion seems out of sight. Maybe the idea of utopia is just that: an idea restricted to the confines of the mind and a place that is impossible or foolish to attempt to realize.

Amanda Bertizlian, July 2015

1 Frederic Jameson, “The Politics of Utopia,” New Left Review 25 (2004), http://www.newleftreview.org/?view=2489.

2 Thomas More, Utopia (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1964), viii.

3 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (London: Macmillan, 1981), 4.

4 Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 5. Originally written between 1960 and 1969, Asthetische Theorie was first published posthumously in 1970.