Nickel Tailings #30, Sudbury, Ontario

1996

Chromogenic color print

Mount Holyoke College Museum of Art

MC 1999.1

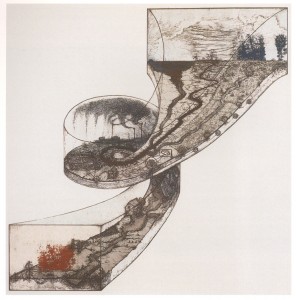

Revival Ramp

1996

Hard-ground etching, soft-ground etching, engraving, photoetching and lithograph on cream-colored Asian paper

Smith College Museum of Art

SC 2002:18

Revival Ramp expands on a conceptual drawing entitled Revival Field, the plan for an experiment using hyperaccumulator vegetation (plants that extract contaminants from soil in order to detoxify polluted land). Revival Ramp illustrates the passage of time through an ecological lens. The narrative of the image begins at the bottom of the print, where Chin has borrowed Leonardo da Vinci’s A Copse of Trees (c. 1500) in order to place us in an idyllic landscape of the past. We follow the ramp through the industrial revolution into the curve of the present-day where we see the “revival field” surrounded by darkness and pollution. Continuing up the ramp, our initial path splits into three possible futures: first, a completely desolate, dystopian wasteland; second, a utopic landscape reclaimed by nature (as represented by the return of da Vinci’s A Copse of Trees); and finally, something that deftly falls between the two.

Memories of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #5, from the series In the Eclipse of Angkor: Tuol Sleng, Choeung Ek, and Khmer Temples

2008

Chlorophyll print and resin

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

MH 2012.5.3

The beauty of this piece comes from its tragic ephemerality. The children whose portraits are on these leaves were executed in a Khmer Rouge torture camp. With photographic positives from the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, Binh Danh uses the chlorophyll process, an alternative photographic method, to transfer the images by placing the positives on the growing leaves and allowing the sun to directly bleach the surfaces. By using the plant’s natural growth, Binh Danh is, in a sense, giving these children a second chance at living and dying naturally. The leaves are picked fresh, but when they are placed in a frame they begin to wither and discolor. Eventually, they will disintegrate altogether and nothing but the vague memory of these children’s faces will be left. Although the piece carries a devastating history, it preserves and elevates the lives that were stolen from the children.

Church at Wounded Knee

1969

Black and white photograph

Univeristy Museum of Contemporary Art, Univeristy of Massachusetts Amherst

Gift of Harvey Krueger

UM 1982.28.1

Elliott Erwitt’s photograph, Church at Wounded Knee, appears peaceful until we become aware of the site’s historical context. The dark, ominous clouds hint at the tragedies that occurred on this land. The church, traditionally read as a symbol of purity and innocence, instead becomes a tombstone: the constant reminder of the massacre of the Sioux in 1890, the deadly protest during the occupation of 1973, as well as the continuing presence of the colonizer. The placement of the church at the top of the frame conveys an imposing nature, while the upward angle enhances its dominance.

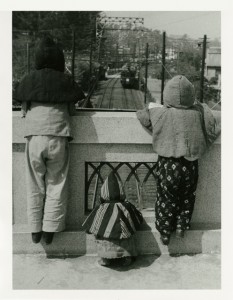

Air Defense Hoods

1945

Silver Gelatin Print

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

AC 2014.60

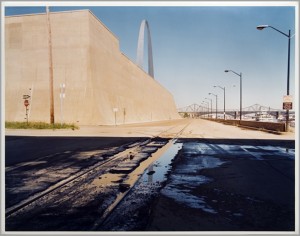

The Arch

1981

Color photograph

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst

UM 1982.1

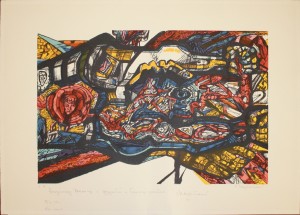

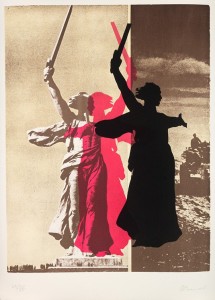

Untitled

1979

Lithograph in colors on medium weight wove paper

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

Gift of Thomas P. Whitney (Class of 1937)

AC 2001.101

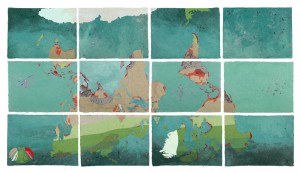

2011

Handmade paper (abaca, cotton, flax, wheat straw, beach and desert sand, soil, marine plastic, dried anchovies, dried shrimp, feather boa, seaweed, dried garden plants, vegetable seeds) and pigment

Smith College Museum of Art

SC 2012:44a-L

This map of the world calculates the direct effects of global warming on human life, predicting the state of the Earth after a 4º C increase of average temperatures. The inverted map flips the traditional notions of Mercator projection maps and demands the viewer to imagine the world beyond this singular viewpoint. Puckett embeds found objects, natural and synthetic, into hand-made paper. The use of abrasive surfaces of sand and soil contrasts the optimistic shades of green and begs the viewer to reconsider their relationship with climate change. Additionally, shades of red create a sense of anxiety while blue provides a sense of peace. Together, the colors spark tensions between hope and fear as well as optimism and pessimism. Future Under Climate Tyranny (F.U.C.T) not only exists as an art object, but also functions as a visual representation of the current global conflict between ignorant resistance and educated adaptation. F.U.C.T. includes both the past and the future—as a map it shows the world as it has been measured and therefore might be seen as a mnemonic device, yet the work also alludes to the world’s future—what we can expect if we do not address global warming.

Sometimes the blind have comforted those that see (L’aveugle parfois a console le voyant) plate 55 from “Miserere” portfolio

1929 (published 1948)

Photogravure, etching and aquatint on heavy weight Arches paper with “Vollard” blindstamp

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

Gift of Irving Vogel (friend of Amherst)

AC 2013.28

This image is a part of Rouault’s series “Miserere” which emphasized his spirituality and the condemnation of France after World War I. Rouault’s monochromatic palette and stylized figures throughout the series emphasize these themes. The scene shows a blind man leading a downtrodden survivor from the darkness of the past toward the light, implying that there are better days ahead. While the series often depicts turmoil, Rouault stressed the prospect of redemption.

Cumbrian Blue(s), Palestine, Gaza

2015

Refined earthenware, lacquer, and gold (kintsugi); transfer printed cobalt blue and lead glaze (pearlware)

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

MH 2015. 12.2

Initially, the imagery on the plate appears to simply represent a type of a widely circulated ceramic plate. Although the history of blue-and-white porcelain is rife with Orientalist and colonialist connotations, the plates are by now ubiquitous and seemingly commonplace. Upon closer inspection, however, the seemingly banal image is transformed and the image of Gaza after an attack by Israel is revealed. Beneath the remnants of a bombed-out building in present-day Palestine, one can still discern the original design: an imagined Orientalist image of the Middle East. The juxtaposition of the antiquated image and the overlaid photograph of Gaza’s current reality illustrates the tensions at play between the utopic and the dystopic.

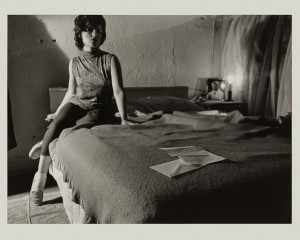

Untitled Film Still #33

1979

Gelatin silver print photograph; 7/10

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

MH 1989.8

Cindy Sherman began her series “Untitled Film Stills” in 1977. In Sherman’s characteristic style, this series examines contemporary female identity. In Untitled Film Still, #33, the image’s narrative qualities work to unsettle the viewer. The woman sits on a bed, foregrounded by an opened letter. In the background, a framed photo of a man looks on. The woman’s face is slightly shadowed, her identity unknown. What does the letter say? Who is the man in the photo? The ambiguity of the scene paired with the intimacy of the bedroom setting results in a contested space where no one is at home.

Ferns

1980

Cibachrome color photograph, 5/20

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst

UM 1981.7

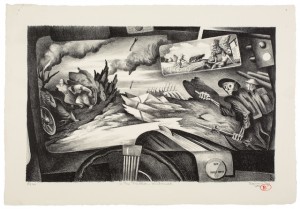

The Thirties, Windshield

1939

Lithograph; ink on paper

Gift of Winifred Glover Spruance (Class of 1925) (wife of the artist)

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

MH 1973.231.I(b).RII

Lurid Sky

1929

Oil on canvas

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Gift of Mrs. John Lee Bunce (Eleanor Howland, Class of 1926)

MH 1953.5.M.PI

Lurid Sky is a surrealistic landscape featuring grey abstracted biomorphic forms floating throughout the space. With an attention to nature, Tanguy created this imagined, atmospheric world in which nothing is familiar. The unnatural yellow background implies a sense of apprehension and threat, while the foreign objects add to the mysterious air, forming a place that is anything but natural. The nonrepresentational nature of this painting makes it difficult for the viewer to relate to. Rather than a livable environment, Tanguy depicts a hostile dreamscape.

The House with the Mezzanine, No. 20

1991

Lithograph on cream paper

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

AC 2010.158

Fan: Solitary Monastery in Mountains

ca. 1860

Drawing

Smith College Museum of Art

Gift of William S. T. Chang

SC 1947:12-3

Yao Zhengyong, a wealthy artist and scholar-official, designed this round fan depicting a mountain landscape and secluded monastery. Around the time of the work’s creation, Yao fled to Taizhou in order to escape the Taiping Rebellion, an internal revolt in southern China. For the artist, the peaceful landscape may have represented an escape from the chaotic world in which he was living. The anachronistic blue-green style was associated with paintings from China’s Golden Age, the Tang Dynasty (618 to 904 CE), and this is another way that the artist chose to retreat from his present situation, Yao used a specific subject and style to imagine a utopia separate from his dystopian reality.