A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

-Walter Benjamin (1940)1

Traditional definitions of utopia and dystopia are often based on the derivation of the terms: utopia as both no place and the good place, and dystopia as no place and the bad place. Despite the focus of these definitions on the spatial and unreal nature of the terms, they are not simply imaginary places. Utopias and dystopias are also temporal; they occur in the present, past, and future. It is important to consider utopias and dystopias not only as imaginary places, but as moments in time, because it is this quality that makes them useful for historical studies.

Utopias and dystopias refer to past events, often nostalgically, and reinterpret them by drawing upon present conditions. Even future-oriented utopias and dystopias, though they do not mention actual events, represent a real possibility which is based on current trends. Thus, utopias and dystopias are not simply delusions, myths, or wishful imaginations, but are grounded in the present. In the introduction to the book Utopia/Dystopia: Conditions of a Historical Possibility, the authors emphasize, “Utopian visions are never arbitrary. They always draw on the resources present in the ambient culture and develop them with specific ends that are heavily structured by the present.”2 Additionally, the information that is provided by utopian and dystopian visions is useful for historians; it allows them to study fears, dissatisfactions, hopes, and desires of the present, past, and/or future in comparison to reality. Finally, according to some thinkers, modernist traditions have become skeptical of history altogether. The past has created unescapable realities that are unrelated to and unhelpful for our current situation.3 The study of utopias and dystopias, through both image and text, is another way to analyze history.

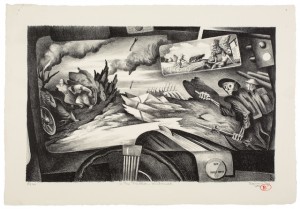

The Thirties, Windshield

1939

Lithograph; ink on paper

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Gift of Winifred Glover Spruance (Class of 1925) (wife of the artist)

Benton Spruance’s print The Thirties, Windshield (1939) is illustrative of the historical and temporal nature of utopias and dystopias. In the print, the viewer is situated behind the wheel. In the rearview mirror, an agrarian scene idealizes the recent past, recalling traditional depictions of utopias as pastoral and idyllic. In front of the car through the windshield, a ravaged landscape depicts an imagined near future. Rubble and smoke pervade the background while two skeletons lead the car forward toward destruction. The print expresses Spruance’s bleak sentiments about the inevitability of future destruction after the end of the 1930’s, and during a time when the world was moving towards another world war. Spruance historicizes the present (1939) by nostalgically alluding to a utopic past–one that is re-imagined and therefore does not exist–and by regretfully predicting a dystopic future. The print reveals how the present attitude of the artist informed his reinterpretation of the 1930s and his prediction for the 1940s.

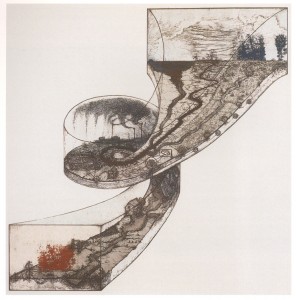

Likewise, Mel Chin’s Revival Ramp (1996) explores a historical progression through an imagined space. The ramp begins at the bottom with Leonardo da Vinci’s A Copse of Trees (c. 1508), a representation of a utopic landscape of the past. It continues upward towards the 18th and 19th century to an imagined ruined landscape contaminated with metals from the Industrial Revolution. The next section is based on the principles of Chin’s Revival Field, a sculptural artwork and experiment which featured collaboration with scientists to test the effectivity of hyperaccumulators–plants which selectively absorb heavy toxic soils as they grow.4 The bend in the ramp contains a drawing of the Revival Field, which attempts to remove the metals and restore the landscape. At the top are three future possibilities: the return of the landscape to its original pristine condition, an industrial, dystopian wasteland, and an unknown future in between the two options.

The Revival Ramp

1996

Hard-ground etching, soft-ground etching, engraving,

photoetching and lithograph on cream-colored Asian

paper

Smith College Museum of Art

In the Revival Ramp, the lack of clarity about the future of the landscape and the environmental concerns underpinning its creation are ideas particular to the current historical moment. The creation of the work and its incorporation of the concepts of the Revival Field reflect the growing awareness of environmental degradation and the desire for its curtailment from the 1990s to the present. Chin describes the Revival Field as “a process and an action and possibly a cure for a situation.”5 Despite Chin’s hope for the project, the presence of multiple futures is indicative of the uncertain outcome of the experiment. This uncertainty is also suggestive of current beliefs about the future and any chance for a realized utopia. Since the fall of communist nations in the 1990s, there has been an increased characterization of the present era as “beyond utopia.” Not only is utopia no longer desirable, it may no longer be possible amid a dystopian reality. Our skepticism leads to the creation of “alternative futures, multiple possibilities and fragmented images of time [that] reflect a lack of confidence about whether and how a better world can be reached.”6 Although Revival Ramp is a purely imagined landscape, its creation is tied to the ideas of a specific historical moment and has bearing on both a present and future reality.

In his 1940 essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Benjamin doubts the ability of history to progress forward and fix the destruction in the past. Both The Thirties, Windshield and Revival Field look back to the past and are dissatisfied with the progression of history. In the former, Benton Spruance predicts an end of a peaceful period and the beginning of a period of war and destruction. In the latter, Mel Chin hopes his project will repair damage to the earth caused by industrial progress, but he is unsure of its success. The two works express skepticism about the hope for a better future in the form of a utopia or a history.

The consideration of the dimensions of time and history work to deconstruct the notions of utopia and the dystopia. The realization of the temporal nature of utopia and dystopia, adds an important layer to the definition of the terms, one that is often lacking. This added lens supports the idea that when either a utopia or a dystopia is situated in the past or future, it conveys useful historical information about the present. Consequently, it can be argued that it is important to study utopias and dystopias not as separate ideas of places, but as simultaneous interrogations of the historical past, the troubled present, and the visionary future, and so should not be written off as merely useless delusions.

Laura Grant, July 2015

1 Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1968), 257.

2 Michael D. Gordin, Helen Tilley, and Gyan Prakash, introduction to Utopia/Dystopia: Conditions of a Historical Possibility (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 4.

3 Hayden White, “The Future of Utopia in History,” Historein: A Review of Past and Other Stories 7, (2007): 13.

4 “Revival Ramp,” accessed July 2, 2015, http://melchin.org/oeuvre/revival-ramp; “Revival Field,” accessed July 2, 2015, http://melchin.org/oeuvre/revival-field.

5 Zoë Ryan and Mel Chin, “A Conversation with Mel Chin,” Log, no. 8 (Summer 2006): 61.

6 Ruth Levitas, “Future Perfect: Retheorising Utopia,” in The Concept of Utopia (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2010), 227.