A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realization of Utopias.

-Oscar Wilde (1891) 1

Political groups often promote visions of utopian futures in order to gain power, but these futures give a great deal of power to the party who created the vision, and who all too often turn the utopian dream into a totalitarian dystopia. Though the ideas behind the vision may not have actually changed, the act of putting the ideas into practice shifts the state of society from working toward improved conditions to the exploitation of the masses to benefit the few. By framing utopias and dystopias in conversation with one another, rather than as opposites, one is able to more easily complicate the distinction between the two. The images in HIDDEN TRUTHS: DISRUPTING UTOPIA serve as a means of understanding those moments in history when utopian plans have led to dystopian realities. They reveal that the concepts behind a planned utopia and the lived dystopia are not so different after all.

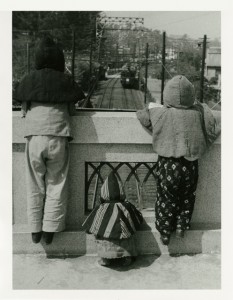

Air Defense Hoods

1945

Silver Gelatin Print

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

We have come to accept that utopias are idealized spaces; yet the desire to realize them often leads to attempts to improve upon existing structures. Throughout time, however, artists have captured this fallacy and demonstrated the untenable nature of utopia. An example of this kind of artistic critique of politics can be found in modern Japanese photography. Before Japan entered the global race for power by joining the Axis powers in the Second World War, the country was widely seen as isolationist.2 Yet, the modern vision to improve and empower the empire cost Japan its peaceful existence and plunged them into a dystopia. In the photograph Air Defense Hoods (1945), Kageyama Kōyō immortalizes the fear that permeated Japanese life after they entered World War II. In the photograph, we see the backs of three small children in padded hoods as they stop to watch an approaching train for the last time before Tokyo is evacuated.3 After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese government recommended that families take apart kimonos to construct these padded hoods in order to protect the populace from the dangers of aerial bombardments, including falling debris. The hoods appear even more futile when contemporary audiences realize this photograph was taken only months before the atom bombs destroyed Nagasaki and Hiroshima in August of 1945. The irony that the Japanese recommended to their citizens to wear slightly padded, homemade hoods to protect themselves from what would be the most devastating attack in human history illustrates the failings of the Japanese government to actually support the utopia they purported to be moving toward. The government’s intentions for joining the war in order to create a powerful, idealized nation had not changed, but the failure of their plan created the worst imaginable situation for the Japanese people.

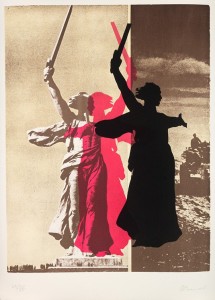

The House with the Mezzanine, No. 20

1991

Lithograph on cream paper

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

Like Kageyama’s critique on imperialism in Japan, Oleg Vladimirovich Vassiliev’s lithograph The House with the Mezzanine, No. 20 (1991) critiques the results of Communism in Russia. This piece was made in 1991, the year the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) collapsed. During the reign of the Soviet Union, Vassiliev worked outside of the realm of the USSR’s official art style, Socialist Realism.4 His use of Evgenyi Vuchetich’s monument to the Battle of Stalingrad, The Motherland Calls (1967), explicitly critiques the Soviet government through the use of their own iconography.5 The statue, erected twenty-five years after the start of the battle, was once the largest monument in the world. Vassiliev uses an image of the figure, juxtaposed with its own silhouette, to convey the ambiguity of three historical moments: the early 1940s when the USSR was engaged in World War II, the middle of the Cold War in the 1960s, and the fall of the Communist government in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The sepia representation of the statue serves its original purpose, a reminder to the bloodiest battle of World War II, often considered the turning point when the Russians made the Allied victory seem possible for the first time. The opaque, black silhouette of the statue condemns the war, pointing to the battlefield. The transparent, cherry red silhouette of the statue, positioned in the center of the frame, faces the opposite direction of the other two figures; she represents the despair at the sight of her fallen citizens. Like any imagined utopia, a Communist society that does not function perfectly will collapse into a dystopia, as seen by the decline and ultimate dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The creator of a utopia is constructing an idealized space. In times of crisis and transition, the utopia becomes an escape or salvation into a time or place that never existed, nor will ever be able to exist. While artists and intellectuals have primarily created these imagined spaces in fictional works, political groups have attempted to construct their own versions of societal perfection in both propaganda and in political planning. Whether benevolently motivated, hypocritical or disingenuous, the strategies of these political groups are not, in fact, pursuing utopia. Groups like the Imperial Japanese government before World War II or the Soviet Union after the war promised their citizens to protect them, and offered visions of a better future, in order to gain and implement their power. In both Kageyama and Vassiliev’s images, the artists depict the destructive results of their respective governments’ failed attempts at realizing their own versions of utopia.

Rhana Tabrizi, July 2015

1 Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism (Auckland, New Zealand: Floating Press, 1891), 27.

2 The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, ed. Amy R. Newland (Amsterdamn, The Netherlands: Hotei Publishing, 2005), s.v. “Ukiyo meisho.”

3 Samuel C. Morse, “Air Defense Hoods,” Five College Museum Database, last modified 2015.

http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=group&f=&s=&record=3

4 “Oleg Vassiliev’s Biography.” Saatchi Gallery. Accessed July 2, 2015. http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/vassiliev_oleg.htm?section_name=breaking_the_ice

5 “The House with the Mezzanine, No. 20,” Five College Museum Database, last modified 2013.

http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=group&f=&s=&record=1