The appropriated image is nomadic, shifting locations over time and constantly adapting. As it enters a new space, its meaning is informed by its frame, and it sheds its old

identity. The same is true for artworks as they enter new spaces: the white cube of the gallery claims to be neutral, but artworks gain new significance through the theses of

curators. Artworks which themselves contain appropriated imagery create a frame within a frame; by entering the object into framing devices inward, the artist acknowledges and forces the viewer to consider framing devices outward as well. Through

appropriation, these artists highlight

institutions of art, including the contested histories of museums, the economy of the art world, and artists’ fame.

In his assemblage

Picasso/Whose Rules? (1991), Wilson reuses the image of Picasso’s famous

painting based on interactions with ethnographic collections and tribal masks to highlight post-colonial problems in the museum institution. Though MoMA’s 1984 show

“Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern went through a long process of praise and then critique for its use of tribal art as illustration, very few new pieces or works have been created that explicitly combine the two sides of the coin, the

“Primitivist” and the “Primitive.” Wilson directly challenges the contested and complicated

history of the source artwork, both its content and exhibition history, by superimposing the tribal mask onto the painting that it illustrated in the MoMA show. By combining them into one work, Wilson obstructs the beauty of the icon with its inspiration, reminding the viewer that the problems of collecting in the

colonial era still haunt the art world today. By installing a video loop with two Senegalese women and his own face into the eyes of the mask, Wilson directly challenges the viewer from both sides of the spectrum: the all-powerful artist/appropriator and the bodies of those who have been exploited. (See also: Fred Wilson,

Mining the Museum (1992-1993).)

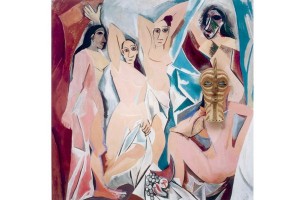

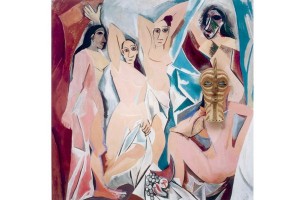

In Jaimie Warren’s

Self-portrait as woman in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso/Online Deceptions by MommaBird (2012), the artist puts herself into the same work as used by Wilson, but for a very different purpose. The original subject of Picasso’s painting was a group of prostitutes in Barcelona, whose faces he eventually abstracted,

increasingly from left to right, into the form of tribal masks. Here, Warren recreates the work on a set, photographing women’s bodies surrounded by brightly colored cardboard cutouts. Where Picasso covers faces with re-creations of tribal masks, Warren puts actual masks of the original painting onto her models. Instead of standing nude, the women in Warren’s piece wear modern dresses and rompers, pouting for an imaginary mirror. By intensifying the colors and pulling in references to our

contemporary age, Warren elevates the average young woman to the status of cultural icon, confronting the viewer with his and Picasso’s own romanticizing gaze on similar women who lived only a century ago.

Suzanne Bloom and Ed Hill similarly appropriate the image of a famous artwork but use it to a different effect. In Mona Lisa Postcard (1979), a mysterious arm holds up a postcard of the Mona Lisa in front of a white building. The postcard is blurred in the foreground of the structure, which stands next to what could be a highway in the rural United States. The architecture of the building is not particularly beautiful or interesting, but when placed next to the famous image of timeless beauty, its aesthetic quality is brought into question. Though the Mona Lisa is used as a signifier of beauty in conversation and theory, Bloom and Hill confront the viewer with the absurdity of comparing everyday objects to the qualities of a classical work of art. The photograph combines the image of the painting with the position an artist uses to gauge perspective, reducing Mona Lisa to a simple swatch for beauty in a landscape alien to the original artwork entirely. (See also: Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective- Mona Lisa (1995-2003)).

Suzanne Bloom and Ed Hill similarly appropriate the image of a famous artwork but use it to a different effect. In Mona Lisa Postcard (1979), a mysterious arm holds up a postcard of the Mona Lisa in front of a white building. The postcard is blurred in the foreground of the structure, which stands next to what could be a highway in the rural United States. The architecture of the building is not particularly beautiful or interesting, but when placed next to the famous image of timeless beauty, its aesthetic quality is brought into question. Though the Mona Lisa is used as a signifier of beauty in conversation and theory, Bloom and Hill confront the viewer with the absurdity of comparing everyday objects to the qualities of a classical work of art. The photograph combines the image of the painting with the position an artist uses to gauge perspective, reducing Mona Lisa to a simple swatch for beauty in a landscape alien to the original artwork entirely. (See also: Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective- Mona Lisa (1995-2003)).

In

Colored Vases (2007-2010), Ai Weiwei displays 2,000 year-old vases from the Han Dynasty, covered by the artist in bright house paint. Ai uses the vases as ready-mades, stripping them of their cultural significance and denying them a place in an ethnographic setting (museum, personal collection, wunderkammer, etc.) where they might usually be found. Similar to his work

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995/2009), Ai exposes the physical fragility of the objects, creating a clear visual metaphor for the fragility so often ignored in China’s grasp on its own historical and cultural narratives. History is constantly rewritten, changing conceptions of historical objects according to new arrangements of significance. Ai shows the viewer that it is not only ideas that can be altered, but the objects on which these ideas are projected. By painting them the bright colors associated with much contemporary art, the artist transforms the works into cultural

currency, giving a once “priceless” object a new, actual price as part of his own collection and available for resale to an entirely new audience and collector. A simple coat of paint rips the objects from their place in the past and places them in Ai’s contemporary catalog of artworks.

Though not a work of visual art, the song

Picasso Baby by Jay-Z has a similar effect in commodifying art as Ai’s

Colored Vases. In his

song, Jay-Z drops the names of artists, not the names of artworks, as a signifier of his own wealth and affluent lifestyle. The rapper switches between the use of these names throughout his song, referencing both

“Basquiat” as a painting in his house, and himself as “the new Jean-Michel.” Jay-Z has acknowledged that he collects art explicitly as a monetary

investment, and his song publicizes his own collection: one does not need to enter his house to know how much money he has. Here, the significance of the work is reduced into its purest form as a commodity; there is no description of which work by “[Francis] Bacon”, “[Mark] Rothko”, or “[George] Condo” the rapper allegedly has in his collection, but dropping the names of the artists serves just as well, if not better, to signify his wealth and cultural currency.

Both of the aforementioned works have been re-appropriated as

events in the past year in very different ways, furthering the change in meaning to old material. On February 17th, 2014, the artist Maximo Caminero made national

headlines when he smashed one of the vases in Ai’s

Colored Vases series, copying the triptych of images in Ai’s

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, both on display at the Pérez Art Museum of Miami. According to various news

sources, Caminero claimed the act was a

performative protest to gain attention for local Miami artists, who felt underrepresented in the wake of the museum’s opening. With his statement, Caminero again appropriated the vases from their original

context and meaning, here using them as a synecdoche for all art made by international art stars like Ai Weiwei. Caminero performed a physically identical act as Ai did in the photographs, yet his actions were deemed “criminal” because he was not already renowned or famous. Though Ai himself is thought of as a transgressive art rebel, Caminero’s actions illuminate the institutions in which Ai operates that keep him and his works on an elevated level, over “local” artists. Caminero’s point came across through the media, when articles lead with the monetary value of the destroyed artwork and a mugshot from his resulting arrest.

Another event of re-appropriation in recent

news occurred at Pace Gallery in July, 2013, as recorded in Mark Romanek’s music video,

“Picasso Baby: A Performance Art Film.” Romanek and Joanna Greenberg Rohatyn, well-known gallerist and art advisor to Jay-Z, orchestrated a live event in Pace’s Chelsea location that was open only to an elite group of people: celebrities and friends of the gallery. Occurring in the aftermath of Marina Abramovic’s

The Artist is Present at MoMA, “Picasso Baby: A Performance Art Film” consisted of a Jay-Z rapping the title song to various celebrities for six hours in a completely white gallery space while fans looked on from the sides. The parallel to Abramovic’s work was very clear, both visually and conceptually: both happened in art spaces, included the public, and were meant to be a rare one-on-one facing with an artist/genius/celebrity. The physical instructions of the piece are nearly identical to any filming of a music video (musician repeats actions over and over, performing/lip syncing his song for hours, while being filmed,) but it has a different effect when transferred to a new frame. Because he was surrounded by fans and in an art space, it’s not “filming,” it’s “performance art.” In the event, the majority of celebrities were of the contemporary art world, including Marina Abramovic herself, Fred Wilson, Lorna Simpson, Rashid Johnson, Lawrence Weiner, and

Jerry Saltz. By putting normal actions in an art context, Jay-Z’s art advisors made his actions appeal to a completely new audience, while simultaneously estranging his usual one. It is the same Jay-Z as at his concerts, performing almost identical actions, but the new frame makes it art and enters it into a lexicon of intellectualism otherwise excluded from his practice.

It is only through the repeated reframing of these images that these artists are able to illuminate for the viewer the invisible frames he occupies: those applied by the collector, the dealer, the curator, the museum director, the gallerist, the docent, the label writer, the architect, etc. Just as Adrian Piper has done with her piece

Ur-Mutter #2 (1989), these artists add layers of meaning to a preexistent image, shepherding it into a new thesis and creating a new effect on the viewer. It is reworked again into an exhibition, and again into an analytical paper. The old information is abandoned to make way for new meaning in both the physical and digital; metadata can be stripped as easily as a watermark on the bottom of a photograph by cropping or quoting. As these images, these digital reproductions, navigate new pathways, they lose and gain information with each step. They do not rest here; they will be dragged and dropped, screenshotted and recopied, until each current identity is shed entirely and they exist as pixels, separate from their original source artwork.

Isadora Reisner 2014

WORKS CITED

COLLECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Primitivist” and the “Primitive.” Wilson directly challenges the contested and complicated history of the source artwork, both its content and exhibition history, by superimposing the tribal mask onto the painting that it illustrated in the MoMA show. By combining them into one work, Wilson obstructs the beauty of the icon with its inspiration, reminding the viewer that the problems of collecting in the colonial era still haunt the art world today. By installing a video loop with two Senegalese women and his own face into the eyes of the mask, Wilson directly challenges the viewer from both sides of the spectrum: the all-powerful artist/appropriator and the bodies of those who have been exploited. (See also: Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum (1992-1993).)

“Primitivist” and the “Primitive.” Wilson directly challenges the contested and complicated history of the source artwork, both its content and exhibition history, by superimposing the tribal mask onto the painting that it illustrated in the MoMA show. By combining them into one work, Wilson obstructs the beauty of the icon with its inspiration, reminding the viewer that the problems of collecting in the colonial era still haunt the art world today. By installing a video loop with two Senegalese women and his own face into the eyes of the mask, Wilson directly challenges the viewer from both sides of the spectrum: the all-powerful artist/appropriator and the bodies of those who have been exploited. (See also: Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum (1992-1993).) increasingly from left to right, into the form of tribal masks. Here, Warren recreates the work on a set, photographing women’s bodies surrounded by brightly colored cardboard cutouts. Where Picasso covers faces with re-creations of tribal masks, Warren puts actual masks of the original painting onto her models. Instead of standing nude, the women in Warren’s piece wear modern dresses and rompers, pouting for an imaginary mirror. By intensifying the colors and pulling in references to our contemporary age, Warren elevates the average young woman to the status of cultural icon, confronting the viewer with his and Picasso’s own romanticizing gaze on similar women who lived only a century ago.

increasingly from left to right, into the form of tribal masks. Here, Warren recreates the work on a set, photographing women’s bodies surrounded by brightly colored cardboard cutouts. Where Picasso covers faces with re-creations of tribal masks, Warren puts actual masks of the original painting onto her models. Instead of standing nude, the women in Warren’s piece wear modern dresses and rompers, pouting for an imaginary mirror. By intensifying the colors and pulling in references to our contemporary age, Warren elevates the average young woman to the status of cultural icon, confronting the viewer with his and Picasso’s own romanticizing gaze on similar women who lived only a century ago. Suzanne Bloom and Ed Hill similarly appropriate the image of a famous artwork but use it to a different effect. In Mona Lisa Postcard (1979), a mysterious arm holds up a postcard of the Mona Lisa in front of a white building. The postcard is blurred in the foreground of the structure, which stands next to what could be a highway in the rural United States. The architecture of the building is not particularly beautiful or interesting, but when placed next to the famous image of timeless beauty, its aesthetic quality is brought into question. Though the Mona Lisa is used as a signifier of beauty in conversation and theory, Bloom and Hill confront the viewer with the absurdity of comparing everyday objects to the qualities of a classical work of art. The photograph combines the image of the painting with the position an artist uses to gauge perspective, reducing Mona Lisa to a simple swatch for beauty in a landscape alien to the original artwork entirely. (See also: Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective- Mona Lisa (1995-2003)).

Suzanne Bloom and Ed Hill similarly appropriate the image of a famous artwork but use it to a different effect. In Mona Lisa Postcard (1979), a mysterious arm holds up a postcard of the Mona Lisa in front of a white building. The postcard is blurred in the foreground of the structure, which stands next to what could be a highway in the rural United States. The architecture of the building is not particularly beautiful or interesting, but when placed next to the famous image of timeless beauty, its aesthetic quality is brought into question. Though the Mona Lisa is used as a signifier of beauty in conversation and theory, Bloom and Hill confront the viewer with the absurdity of comparing everyday objects to the qualities of a classical work of art. The photograph combines the image of the painting with the position an artist uses to gauge perspective, reducing Mona Lisa to a simple swatch for beauty in a landscape alien to the original artwork entirely. (See also: Ai Weiwei, Study of Perspective- Mona Lisa (1995-2003)). “Basquiat” as a painting in his house, and himself as “the new Jean-Michel.” Jay-Z has acknowledged that he collects art explicitly as a monetary investment, and his song publicizes his own collection: one does not need to enter his house to know how much money he has. Here, the significance of the work is reduced into its purest form as a commodity; there is no description of which work by “[Francis] Bacon”, “[Mark] Rothko”, or “[George] Condo” the rapper allegedly has in his collection, but dropping the names of the artists serves just as well, if not better, to signify his wealth and cultural currency.

“Basquiat” as a painting in his house, and himself as “the new Jean-Michel.” Jay-Z has acknowledged that he collects art explicitly as a monetary investment, and his song publicizes his own collection: one does not need to enter his house to know how much money he has. Here, the significance of the work is reduced into its purest form as a commodity; there is no description of which work by “[Francis] Bacon”, “[Mark] Rothko”, or “[George] Condo” the rapper allegedly has in his collection, but dropping the names of the artists serves just as well, if not better, to signify his wealth and cultural currency.