Adrian Piper’s Ur-Mutter #2 (1989) is a complex and difficult image that deserves to be studied in multiple contexts. Our examination of this work in a diverse range of physical and digital spaces has deeply informed our curatorial practice. Throughout this exhibition, we interrogate the appropriative work of contemporary artists and curators. Like Adrian Piper’s Ur-Mutter #2, each image selected for this essay requires pulling apart the layers of appropriated content and critically examining the new meaning generated by that act of layering. Using the methods of addition, erasure, combination, and reproduction, each artist collapses multiple narratives into one contemporary moment: the viewer’s present. This iconographic densification subverts the original image’s authority as a record of Truth. In these works, each layer of content must be considered in its original context, in its appropriated context, and in the context of the viewer. Thus, the viewer’s interpretation becomes part of the content, and history, of the image.

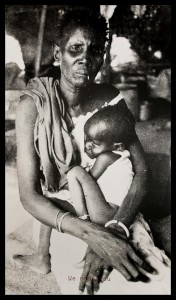

Adrian Piper appropriates Peter Turnley’s photograph of a Somali woman and child to interrupt the propagation of a colonial narrative, one that categorizes the subject within one of many limiting roles, such as the archetypal representation of the omnipresent Earth mother, the Madonna and child, the poverty-stricken African, or the oppressed woman. The subject in Piper’s reproduction of Turnley’s photojournalistic image and her addition of the text “We made you” denies categorization. Rather, she implicates the viewer by “exhaust[ing] the range of available conceptual interpretations” of the woman and child.(1) The work in this way serves as a mirror through which the viewer’s objectifying gaze is reflected; indeed, framed in reflective glass, we are unable to view the piece without seeing our own visage reflected in the image. Ur-Mutter #2 forces us to analyze what these roles symbolize and challenges us to consider: Who created these stereotypes? Who owns them? Who perpetuates them?

Kara Walker employs similar tactics in her 2005 alteration of an illustration from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War: Contemporary Accounts and Illustrations from the Greatest Magazine of the Time (1866). The editors claimed to give an account of the Civil War with unbiased accuracy.(2) Walker complicates their story in Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats, from the series Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) by placing a solid black silhouette directly onto the illustration’s surface. She incorporates the original Harper’s image into her visual vocabulary; billowing smoke from the ship in the distance becomes a stand-in for the silhouette’s excrement and her bare foot is an object of desire for the child crawling in the foreground. Walker’s iconic lexicon is replete with such grotesque imagery. She draws upon the “vicious humor of racialized stereotypes” to disrupt the historical narratives that perpetuate them.(3) Walker undermines our view of what this illustration recounts by confronting us with a caricatured version of what we may not have even noticed was absent.

The silhouette exists in a liminal space between a superimposition on, and integration in, the scene; caught between two contexts – our contemporary moment and that depicted in Harper’s.(4) Its placement just above the illustration’s inscription obscures the image but not the text, thus becoming an alternate title to the scene. Just as the viewer can no longer separate Peter Turnley’s image from Piper’s “We made you,” Harper’s account of this Civil War narrative is now part of the same history as Kara Walker’s figure. Both artists powerfully remind the viewer of this historical conflation. Adrian Piper’s Ur Mutter #2 must be displayed with the photo credit given to Peter Turnley, though Turnley granted permission for her to use the image in this way, just as Kara Walker deliberately chooses to remind the viewer of the source of her image in both the title of the artwork and the legibility of the title of the original drawing.

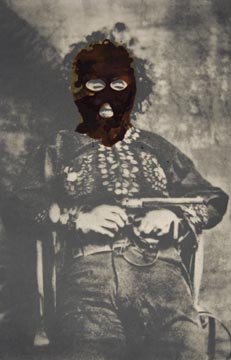

In Bloody Bill Anderson Balaclava (2006), Adam Helms  also simultaneously erases and accentuates appropriated content through surface alteration. Helms reproduces a photograph of “Bloody” Bill Anderson, a leader of Confederate guerillas in Civil War Missouri, adding an iconic symbol, the balaclava. With this addition, Helms brands Bill Anderson as an archetypal villain, thereby contextualizing him within a lineage of outsiders.

also simultaneously erases and accentuates appropriated content through surface alteration. Helms reproduces a photograph of “Bloody” Bill Anderson, a leader of Confederate guerillas in Civil War Missouri, adding an iconic symbol, the balaclava. With this addition, Helms brands Bill Anderson as an archetypal villain, thereby contextualizing him within a lineage of outsiders.

also simultaneously erases and accentuates appropriated content through surface alteration. Helms reproduces a photograph of “Bloody” Bill Anderson, a leader of Confederate guerillas in Civil War Missouri, adding an iconic symbol, the balaclava. With this addition, Helms brands Bill Anderson as an archetypal villain, thereby contextualizing him within a lineage of outsiders.

also simultaneously erases and accentuates appropriated content through surface alteration. Helms reproduces a photograph of “Bloody” Bill Anderson, a leader of Confederate guerillas in Civil War Missouri, adding an iconic symbol, the balaclava. With this addition, Helms brands Bill Anderson as an archetypal villain, thereby contextualizing him within a lineage of outsiders.As Helms writes:

I’m interested in these figures as they present themselves as actors in their own mythology, or how they define the contemporary periods they are involved in by opposition to, rather than inclusion within, an established society or order. They are in many ways, I suppose, the underdog with whom I identify and support.(5)

Bill Anderson becomes an actor in his own mythology through Adam Helms’s presentation of him as an archetype.

In Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos (2009) Rashid Johnson also identifies with his subject, appropriates the aesthetic style, techniques and symbols of other artists and histories, and writes a new mythology. The portrait restages the style of Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee and claims to depict Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice. The image is then overlaid with graffiti – a symbol of a sniper crosshair appropriated by the American hip-hop group Public Enemy as the logo for the cover of their 1989 single Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos. Yet another appropriated layer – in this case textual – is created when considering this work within Johnson’s series The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club. This series is a commentary on Alain Locke’s 1925 essay New Negro, An Interpretation, the writing of W.E.B. Dubois, Harold Cruse and others. Through this densification, Johnson places post-black art on this timeline – and the layers accumulate to represent the most current version of the “New Negro.”(6)

In Thurgood in the Hour of Chaos (2009) Rashid Johnson also identifies with his subject, appropriates the aesthetic style, techniques and symbols of other artists and histories, and writes a new mythology. The portrait restages the style of Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee and claims to depict Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice. The image is then overlaid with graffiti – a symbol of a sniper crosshair appropriated by the American hip-hop group Public Enemy as the logo for the cover of their 1989 single Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos. Yet another appropriated layer – in this case textual – is created when considering this work within Johnson’s series The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club. This series is a commentary on Alain Locke’s 1925 essay New Negro, An Interpretation, the writing of W.E.B. Dubois, Harold Cruse and others. Through this densification, Johnson places post-black art on this timeline – and the layers accumulate to represent the most current version of the “New Negro.”(6)Yet, rather than an accidental or causal accumulation, Rashid Johnson asserts his own agency over the different historical narratives that the image references, and relates them directly to his own identity and artistic practice.(7) Like Kara Walker and Adrian Piper, Johnson uses appropriation as a tool to debunk conventional ways of seeing blackness.

Fred Wilson uses the history of cultural appropriation in art, and the institution’s perpetuation of colonialism, to inform his contemporary appropriative work. In Picasso/Whose Rules (1991), Wilson reproduced Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (originally completed in 1907) and covered one of the faces with a tribal mask. A videotape of Wilson and two Senegalese people was placed behind the mask asking the viewer, “If my contemporary art is your traditional art, is my art my cliché?” and “If your contemporary art is my traditional art, is your art my cliché?”(8) Using the symbol of the mask as a metaphor for institutionally created hierarchies of value, Wilson criticizes Picasso’s cultural appropriation of ‘tribal’ imagery and the museum’s appropriation of ‘primitive’ cultures. The disruption of Les Demoiselles D’Avignon forces the viewer to confront their own complicity in the construction of colonialist narratives.

Fred Wilson uses the history of cultural appropriation in art, and the institution’s perpetuation of colonialism, to inform his contemporary appropriative work. In Picasso/Whose Rules (1991), Wilson reproduced Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (originally completed in 1907) and covered one of the faces with a tribal mask. A videotape of Wilson and two Senegalese people was placed behind the mask asking the viewer, “If my contemporary art is your traditional art, is my art my cliché?” and “If your contemporary art is my traditional art, is your art my cliché?”(8) Using the symbol of the mask as a metaphor for institutionally created hierarchies of value, Wilson criticizes Picasso’s cultural appropriation of ‘tribal’ imagery and the museum’s appropriation of ‘primitive’ cultures. The disruption of Les Demoiselles D’Avignon forces the viewer to confront their own complicity in the construction of colonialist narratives.

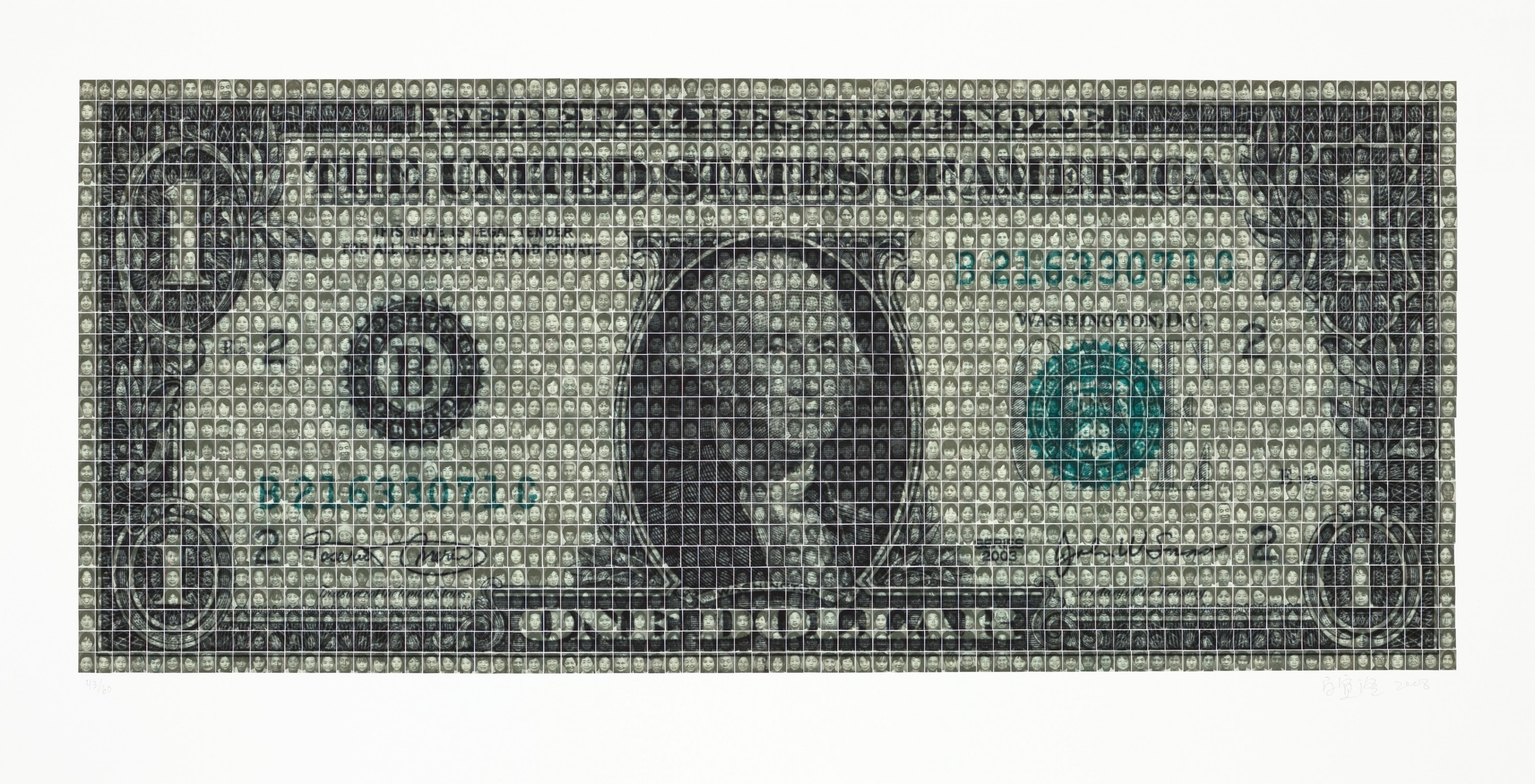

Instead of a mask, Bai Yiluo appropriates the symbol of the US dollar as the marker of a globalized economy. Initially, Untitled (US Dollar),(2008) appears to be an image of a dollar bill, but a closer look reveals that it is a composite image assembled with discarded ID photos of Chinese laborers. By putting a face to the constitution of currency, Bai implicates the viewer in the exploitation of humans for profit.

Instead of a mask, Bai Yiluo appropriates the symbol of the US dollar as the marker of a globalized economy. Initially, Untitled (US Dollar),(2008) appears to be an image of a dollar bill, but a closer look reveals that it is a composite image assembled with discarded ID photos of Chinese laborers. By putting a face to the constitution of currency, Bai implicates the viewer in the exploitation of humans for profit.

The manipulation of scale in this work suggests the hierarchy of value within this system, placing the individual at the base of the ladder as the most disposable element and the dollar as the most valuable.

Through the appropriation and alteration not only of borrowed images, but of multiple layers of content, these artists challenge our acceptance of the historical narratives they critique. The resulting image is not the sum of its parts, but an amalgamation of the original content, the appropriated content, and the vacillation between two: a collapsed history in which colonial narratives become self-reflexive.

Laura Ritchie 2014