“Fields of Vision” explores the cultural construction of the landscape and the constructed perception of the photograph. By presenting photographs that allow viewers to visualize this given trait of landscape, they are able to understand a scene differently than if they were gazing at that stretch of land in person. The photographs included in this exhibition not only depict constructed landscapes—they are constructed landscapes, altered not only through direct human interaction and intervention with the environment, but also through the imposition of an aesthetic. Through these photographs and their accompanying texts there are several fundamental questions that we address: How do we see and understand photographs? How do we see and understand landscapes? How do these two experiences differ? And ultimately, how do photographers and their photographs construct visual, cultural, and ideological understandings and experiences of the landscape?

Fields of Vision

Photography, (In)visibility, and the Constructed Landscape

Curatorial Essay

To photograph a landscape is to create a landscape. Landscapes, which we see as natural, “real” spaces, are in fact created, mediated, and naturalized by the act of transferring a precisely framed, selected view from the artist’s field of vision onto a canvas or photographic emulsion. And although it is through art that we see landscapes, the idea of the landscape is not contained by the bounds of the frame. The idea of the landscape has escaped the realm of the aesthetic and become a permanent resident of the experiential, altering the way we actively see and construct the world around us. As John Berger observes, in “the first period of its existence photography offered a new technical opportunity; it was an implement. Now, instead of offering new choices, its usage and its ‘reading’ [have become] habitual, an unexamined part of modern perception itself.”1 A landscape as formed in the mind of the viewer is a system of signs and symbols whose meanings go beyond simply “a pretty view” or “trees and rocks.” These are not simply dictionary definitions and visual décor; the landscape is “read” not as a material but a cultural, ideological, experiential, and temporal construction.

Landscape is a fundamentally imagined and constructed phenomenon in many different ways. In his essay “The Beholding Eye,” D.W. Meinig identifies a problem with landscape: when “we gather together and look in the same direction in the same instant, we will not—we cannot—see the same landscape,” Meinig argues that the objects in and of a landscape “take on meaning only through association; they must be fitted together according to some coherent body of ideas. Thus we confront the central problem: any landscape is composed not only of what lies before our eyes but what lies within our heads.”2 To explain this issue, Meinig points to ten lenses through which landscapes are constructed: as nature, as habitat, as artifact, as system, as problem, as wealth, as ideology, as history, as place, and as aesthetic. This construction is purely experiential, with each individual pressing any number of these frames into service when confronted with a scene. But, even more problematically, it is not only through human vision that the landscape is constructed, but through an actual lens as well.

When discussing the photograph as a landscape, it is essential to consider the fact that photography and the human eye each construct images in different ways. The human eye is always selective: what we see is filtered through our preconceptions and biases and ultimately dependent on our subjective memory. But photographs work not only through this subjective gaze—they work through the filter of the photographer’s eye as well because, as Estelle Jussim and Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock point out, “pictures themselves are the result of a complex of technological factors comingled with intellectual aspirations, narrative propensities, aesthetic expertise, and symbolism.” Furthermore, “photography is by no means a universal language, available to all times and places without the troublesome interferences of ethnocentric and tempocentric biases.”3 Thanks to the filters and biases implicit in the medium, the act of looking at a photograph is always different than looking at what the image has captured in person, in situ.

While both the photographer’s and the viewer’s eye may discriminate, the lens that has created the photograph does not, giving the viewer a way of looking at what can’t be seen with the human eye alone—a subjective gaze upon an image that may be frozen in form but never in meaning. Edward Weston, in his essay “Seeing Photographically,” makes the point that photography “is basically too honest a medium for recording superficial aspects of a subject…But the camera’s innate honesty can hardly be considered a limitation of the medium, since it bars only that kind of subject matter that properly belongs to the painter.” Instead, “It enables him to reveal the essence of what lies before his lens with such clear insight that the beholder may find the recreated image more real and comprehensible than the actual object.”4 This is an irony fundamental to photographs: only through their uncompromising capture of “what is there” do we actually see what is there. Only once it has been photographed do we see a landscape, never before. Photographs allow us to see beyond our own limited fields of vision and into the otherwise invisible: the constructed nature of landscape.

-Jacob Edwards

1 John Berger, About Looking (New York: Pantheon, 1980), 49.

2 D. W. Meinig. “The Beholding Eye,” in Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes, ed. D. W. Meinig (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), 33-34.

3 Estelle Jussim and Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock, Landscape as Photograph (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 5.

4 Edward Weston, “Seeing Photographically,” in Classic Essays On Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg (New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980), 174.

The Functionality of the Digital Exhibition

Fields of Vision is centered around ways of seeing and framing an image. It is thus appropriate that the exhibition space–this webspace–reflect and expand upon altered ways of viewing. Images are superimposed over themselves, providing their own backgrounds. Bands of color create aesthetic relationships between images and provide context for these relationships. Accordion bars drop down and carousel slideshow elements alter the order of viewing: image to documentation, image to text to documentation. The web presence is one of exploration, learning, altered vision, and shifting perception. How does the order in which we receive information change our reflections upon that information? How do textual elements interact with the material objects—the juxtaposed photographs? The supposed truth of any given landscape is fundamentally altered not only by the photographs, but also by the way that we move through the space of the web.

The Disappearance of Nature, the Persistence of the Sublime

The concept of “nature” is surely contentious—it has been debated throughout history in scientific, artistic, philosophical, social, political, and religious realms. This exhibition tackles one of the most challenging debates about landscape imagery: that nature does not exist independently of humankind’s relationship with and constructions of it. In focusing on landscape photography, we are exploring the relationships between the photographer and their subject. Nature is present in many of the photographs that constitute this exhibition. It is not that the photographers have managed the impossible, to locate and document the essence of nature. Rather, “nature” has a personal significance for each of them, and it has influenced their artistic practices to varying degrees. Throughout this exhibition, we use the word “nature” (and its synonyms) without qualification; consider it a less clunky substitute for “what one thinks of as nature,” rather than an uncomplicated acceptance of nature as the wilderness, or untamed animals, or all the other non-human stuff located someplace elsewhere.

Photography is one of the newest art forms, and one whose genesis is inextricably woven with industry, the same amorphous force responsible for so much of our environmental crisis. Yet, many of the most powerful contemporary expressions of environmental concern are photographic. The materiality of photography, in its chemical splendor, causes pollution. Via the same act, environmentally conscious photographers increase their impact and disseminate information that could catalyze meaningful action. It is tempting to dismiss them as hypocrites. However, recognizing the complex tensions inherent in their practice can actually be productive. The validity of an environmentally conscious photographer’s message does not hinge on holding them to an impossible ethical standard. Sure, everyone is culpable in a crisis so systemic and entwined with everyday habits. However, that does not mean everyone is either willfully ignorant or a sanctimonious phony. If we respect the photographer’s intelligence and morality, and accept that they have reflected on the issues they depict, it becomes clear that they are, in fact, grappling with their place in the environment through their art. Drawing attention to a problem does not mean condemning everyone else and exempting oneself. To draw out this distinction, it is helpful to place contemporary landscape photography within the artistic tradition of landscape as a whole.

Compared with the present, the European and American landscape painting of the nineteenth century seems to represent an idyllic time for the natural world. Nature was ostensibly unspoiled, flourishing, something with which humans had a cooperative and mutually fulfilling relationship. Two of the three prevalent aesthetic approaches to landscape, the pastoral and the picturesque, supported this notion, even going so far as to suggest human mastery of nature. Today, paintings by artists like John Constable in England or Thomas Cole in the United States seem quaint and inapplicable to any continuations of the tradition. The third approach, the sublime, illustrated anxieties about nature’s overwhelming power, its potential not so much to master us as swallow us whole, as works by J.M.W. Turner or Frederich Church famously exemplify.

In the work of contemporary landscape photographers like Edward Burtynsky, the sublime power of nature remains a force. However, it is a power that bears obvious human influence. Human activity has had a dramatic impact on the natural world, but the extent of the impact does not mean humans have mastered nature. Rather, these landscapes of our making have become unwieldy, taken on lives of their own, and we confront with deep anxiety the possibility that they will prevail over us. Burtynsky describes how he confronts this in his work as “the inversion of the sublime, where humans have become the omnipresent force, and we are dwarfed within our own creation.”1 As with so much of his work, Nickel Tailings #30 is dissonant, representing a tension not only between beauty and ugliness, but also between the safety of aesthetic distance and the harsh reality depicted. Burtynsky draws attention to the consequences of the products we use that we are unlikely to think about and otherwise would not see. Within this landscape, he highlights the aesthetic beauty we would probably not experience in its vast barrenness in the unlikely scenario we were able to be in this tragic place firsthand. The beauty of the photograph is deeply troubling; it appears unearthly. Stephen Greenblatt writes of “resonance and wonder,” the two reactions we have to works of art seen in museums. Resonance is the meaning of the work, its associations and context, while wonder is the aura that draws the viewer in, that which causes visceral, even transcendent responses.2 The resonance of Burtynsky’s environmental photographs can create ambivalence, even shame in the viewer who has felt their wonder. The viewer may, in fact, feel indicted—what does it mean that this photograph not only seems beautiful to me, but unlike anything I can imagine happening to this planet? Am I especially complicit in the comfort of this art gallery? Beyond guilt, there is resignation to the awareness that the scene is similar to so many others out of sight. These are the stunning vistas of our time. The terrible enormity of it all is enough to make one collapse, but that’s true of the environmental crisis as a whole. It truly is sublime, but that does not make it a public service announcement.

-Ethan Spielman

1 “Interview with Edward Burtynsky.” in Perspecta 41 (2008): 72-73, 153-159

2 Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. by Ivan Karp and Steven Levine, 42-56. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 1991.

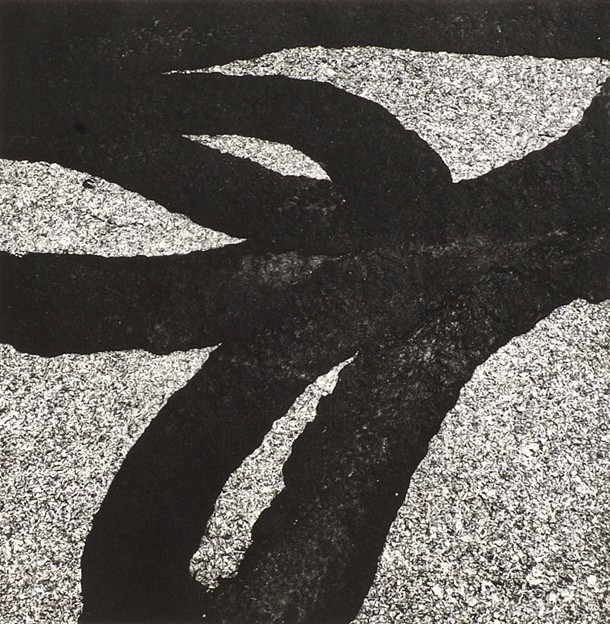

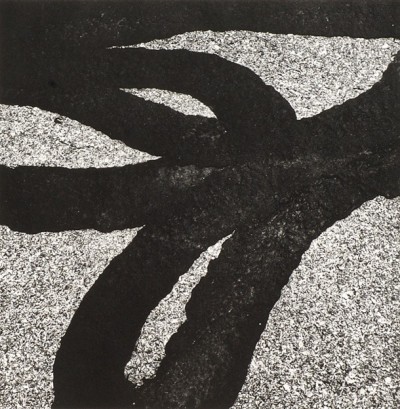

Westport 87

Aaron Siskind (American 1903-1999)

Westport 87 comes from Siskind’s Tar Abstracts portfolio, a series of photographs documenting the fruits of his search for “poetic” tar on asphalt roads.

1988

Gelatin silver print

14 x 14 in

Smith College Museum of Art: SC 2003:43-3d

Gift of Lynn Hecht Schafran (Class of 1962)

Corn Sign with Storm Cloud, near Greensboro, Alabama, 1977

William Christenberry (American born 1936)

William Christenberry offers the viewer an unconventional landscape that exhibits sublime qualities through its retrospective content and an avowal of time’s passing.

1977

Ektacolor print photograph

3 1/4 x 4 7/8 in

Smith College Museum of Art: SC 1988:45-1

Purchased with the gift of the Smith College Museum of Art Visiting Committee in honor of Charles Chetham

The Bar B-Q Inn, Greensboro, Alabama

William Christenberry (American born 1936)

William Christenberry reminds us that time is a contributor to the construction of a landscape.

1976

Color print

5 3/16 in x 4 7/8 in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 1989.56

Bequest of Richard Templeton (Class of 1931)

Sandhill Cranes over Brazos River, Texas

William Garnett (American 1916-2006)

Through his use of aerial photography, William Garnett offers the viewer an abstract view of a landscape by eliminating the horizon line.

1975

Color photograph, portfolio edition 18

12 9/16 x 19 1/16 in

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst: UM 1984.30.6

Gift of Stephen Roth

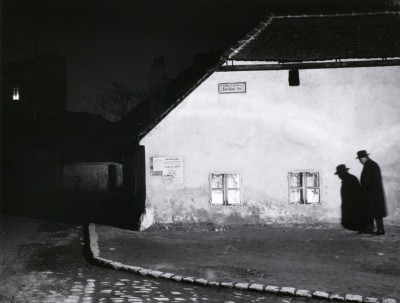

Bocskay Tér, Budapest

André Kertész (Hungarian-American 1894-1985)

Kertész is known particularly for his photographs of Paris taken in the 1920s, though samples of his work in Budapest, his original home, remain.

from the “Hungarian Memories” series

1914

Black and white photograph

7 1/4 x 9 11/16 in

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst: UM 1978.65

Purchased with funds from the Alumni Class of 1928 and a National Endowment for the Arts Museum Purchase Plan Grant

2012 negative; 2014 print

Epson Ultrachrome K3inkset on Canson Infinity Baryta Photographique paper

11 in x 16 1/2 in

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum: MH 2014.41.3

Gift of the Artist

Silvas Oil Company Station, Ventura

Robert von Sternberg (American born 1939)

This photograph joins two of von Sternberg’s chief fixations: humankind’s invasion of the natural world, and that distinctly American form of tourism—the road trip.

2004

Digital chromogenic print

12 1/16 x 16in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 2010.181.1

Gift of Mark and Elaine Connelly

Delirium (Alessandria, Italy)

Jill Mathis (American born 1964)

In her series “Parallel Text,” Jill Mathis pairs her arresting black and white images with single words that have been embedded within the photograph in order to generate deeper meanings.

Montresor

Sally Gall (American born 1956)

Sally Gall often works with infrared film to construct a scene that, without this photographic technology, would be invisible to the human eye.

1988

Gelatin silver print

15 1/16 x 15 1/8in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 1999.141.12

Gift of Stanley and Diane Person

1974 (print 1976)

Black and white photograph

13 13/16 x 13 13/16 in

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst: UM 1978.53

Purchased with funds from the Alumni Class of 1928 and a National Endowment for the Arts Museum Purchase Plan Grant

Landscape, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Frank Gohlke (American born 1942)

As one of the ten photographers of the landmark “New Topographics” exhibition of 1975, Frank Gohlke is immediately concerned with capturing the seemingly mundane in the environment.

Lane Manned, New York City, 1985

Marilyn Bridges (American born 1948)

Marilyn Bridges’s work demonstrates how a dramatic change in perspective can abstract a seemingly familiar environment.

1985

Gelatin silver print

14 13/16 x 18 3/4 in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 1995.66.16

Gift of Stanley and Diane Person

Mt. Rushmore, South Dakota

Lee Norman Friedlander (American, born 1934)

In the 1960s, Friedlander began his exploration of America’s “social landscape,” the stuff of lived experience.

1969 (print, ca. 1976)

Photograph

Gelatin silver print

South Dakota

7 1/2 in x 11 1/4 in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 1985.8.42

Gift of Steven M. Jacobson (Class of 1953)

Idaho, 1972

Lee Norman Friedlander (American, born 1934)

Like his photograph Mt. Rushmore, South Dakota, Friedlander’s Idaho, 1972 creates a landscape out of “obstacles,” his dedication to the theme much more apparent in this composition.

1972 (print, ca. 1978)

Photograph

Gelatin silver print

Idaho

7 3/8 x 11 1/8 in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 1985.8.32

Gift of Steven M. Jacobson (Class of 1953)

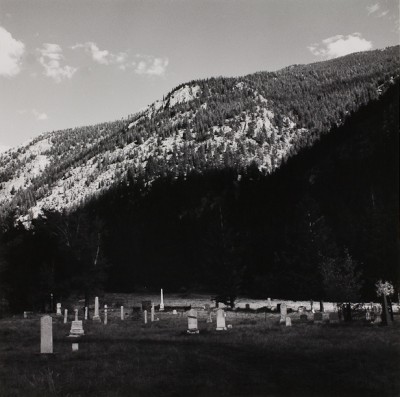

Pioneer Cemetary, Near Empire

Robert Adams (American born 1937)

Adams’s photos may initially suggest development overpowering its surroundings, or at least a disharmonious relationship, but that is not the whole story.

1969

Gelatin silver print

6 x 6 in

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum: MH 2000.8.8

Gift of Marilyn and Wilson S. Mathias

2013

Gelatin silver print

48 x 58 in

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst: UM 2013.58

Purchased

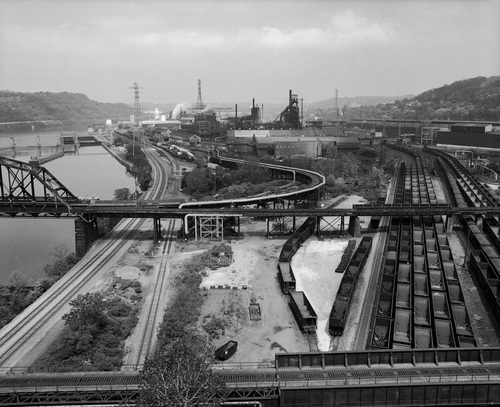

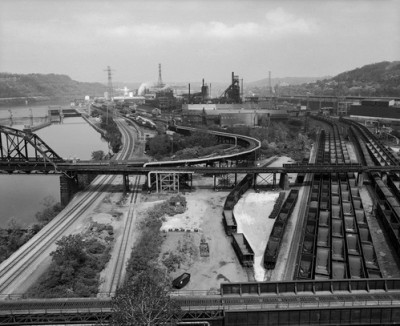

U.S.S. Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Monongahela River

LaToya Ruby Frazier (American, born 1982)

Originally appearing in LaToya Ruby Frazier’s first monograph The Notion of Family, this photograph is inseparable from its sequence in the book.

Straw and Bramble, Redding, Connecticut

Paul Caponigro (American, born 1932)

Caponigro focuses on encouraging healthy, creative dialogues about art and the environment, as well as the celebration of both individualism and diversity.

1970

Cibachrome photograph

13 5/16 x 19 5/8in

University Museum of Contemporary Art, University of Massachusetts Amherst: UM 1984.28.2

Gift of Ronald and Nola Sher

from the Manhattan portfolio

2004

Printed by Rosemary Kress and plates made by Jon Goodman

Photogravure on Somerset paper

13 x 10 3/16in

Smith College Museum of Art: SC 2005:2-5

Purchased with the fund in honor of Charles Chetham

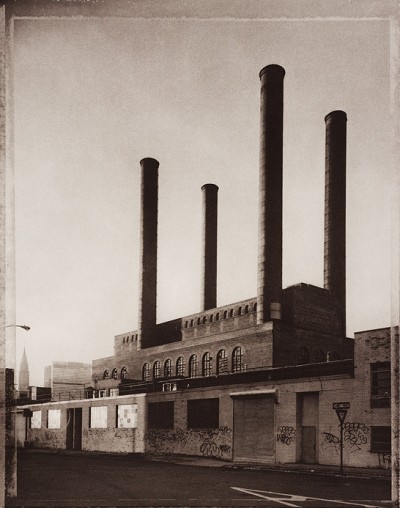

Smoke Stacks Variation

Tom Baril (American born 1952)

Tom Baril has manipulated a contemporary image to resemble one much older, adding a certain aura to a banal location.

n.d.

Gelatin silver print mounted on paperboard

Greece

10 5/16 x 10 5/16 in

Smith College Museum of Art: SC 1943:15-2a

Purchased

The Propylaea from the Center Door Looking West

Paul Cordes (American, 1893-?)

This photo is part of a series that Cordes took of Ancient Greek monuments.

from ‘One Hundred Views of Ginza at Night’

December 7, 1932

Gelatin silver print

9 ½ x 13 in

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College: AC 2014.49

Museum purchase with gift of funds from Scott H. Nagle (Class of 1985) in honor of Samuel C. Morse, Howard M. and Martha P. Mitchell Professor of the History of Art and Asian Languages and Civilizations, and the Richard Templeton (Class of 1931) Photography Fund

From the Top of the Asahi Newspaper Building

Kageyama Kōyō (Japanese 1907-1981)

Initially, Kageyama Kōyō’s view of the city of Tokyo is one of urban beauty; the two figures standing on top of a building gaze over the twinkling lights of the street below.

Image Gallery

-

Edward Burtynsky, <i>Nickel Tailings #30</i>, 1996

Edward Burtynsky, <i>Nickel Tailings #30</i>, 1996 -

Aaron Siskind, <i>Westport 87</i>, 1988

Aaron Siskind, <i>Westport 87</i>, 1988 -

William Christenberry, <i>Corn Sign With Storm Cloud, near Greensboro, Alabama</i>, 1977

William Christenberry, <i>Corn Sign With Storm Cloud, near Greensboro, Alabama</i>, 1977 -

William Christenberry, <i>The Bar B-Q Inn, Greensboro, Alabama</i>, 1976

William Christenberry, <i>The Bar B-Q Inn, Greensboro, Alabama</i>, 1976 -

William Garnett, <i>Sandhill Cranes Over Brazos River, Texas</i>, 1975

William Garnett, <i>Sandhill Cranes Over Brazos River, Texas</i>, 1975 -

André Kertész, <i>Bocskay Tér, Budapest</i>, from the <i>Hungarian Memories Series</i>, 1914

André Kertész, <i>Bocskay Tér, Budapest</i>, from the <i>Hungarian Memories Series</i>, 1914 -

Jill Mathis, <i>Delirium (Alessandria, Italy)</i>, 2004

Jill Mathis, <i>Delirium (Alessandria, Italy)</i>, 2004 -

Robert von Sternberg, <i>Silvas Oil Company Station, Ventura</i>, 2012

Robert von Sternberg, <i>Silvas Oil Company Station, Ventura</i>, 2012 -

Sally Gall, <i>Montresor</i>, 1988

Sally Gall, <i>Montresor</i>, 1988 -

Frank Gohlke, <i>Landscape, Albuquerque, New Mexico</i>, 1974

Frank Gohlke, <i>Landscape, Albuquerque, New Mexico</i>, 1974 -

Marilyn Bridges, <i>Lane Manned, New York City, 1985</I>, 1985

Marilyn Bridges, <i>Lane Manned, New York City, 1985</I>, 1985 -

Lee Norman Friedlander, <i>Mount Rushmore</i>, 1969

Lee Norman Friedlander, <i>Mount Rushmore</i>, 1969 -

Lee Norman Friedlander, <i>Idaho, 1972</i>, 1972

Lee Norman Friedlander, <i>Idaho, 1972</i>, 1972 -

Robert Adams, <i>Pioneer Cemetery, Near Empire, Colorado</i>, 1969

Robert Adams, <i>Pioneer Cemetery, Near Empire, Colorado</i>, 1969 -

LaToya Ruby Frazier, <i>U.S.S. Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Monongahela River</i>, 2013

LaToya Ruby Frazier, <i>U.S.S. Edgar Thomson Steel Works and Monongahela River</i>, 2013 -

Paul Caponigro, <i>Straw and Bramble, Redding, Connecticut</i>, 1970

Paul Caponigro, <i>Straw and Bramble, Redding, Connecticut</i>, 1970 -

Tom Baril, <i>Smoke Stacks Variation</i>, 2004

Tom Baril, <i>Smoke Stacks Variation</i>, 2004 -

Paul Cordes, <i>The Propylaea from the Center Door Looking West</i>, no date

Paul Cordes, <i>The Propylaea from the Center Door Looking West</i>, no date -

Kageyama Koyo, <i>From the Top of the Asahi Newspaper Buildings</i>, 1932

Kageyama Koyo, <i>From the Top of the Asahi Newspaper Buildings</i>, 1932

Bibliography

Andrews, Malcolm. Landscape and Western Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Atencia-Linares, Paloma. “Fiction, Nonfiction, and Deceptive Photographic Representation.”

Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism 70.1 (2012): 19-30.

Berger, John. About Looking. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

Berque, Augustin. Thinking Through Landscape. London: Routledge, 2014.

Boetzkes, Amanda. “Waste and the Sublime Landscape.” Canadian Art Review 35.1 (2010): 22-31.

Crang, Mike. “Tristes Entropique: Steel, Ships and Time Images for Late Modernity.” In Visuality/Materiality: Introducing a Manifesto for Practice, edited by Gillian Rose and Divya P. Tolia-Kelly, 59-73. London: Ashgate, 2012.

Davis, Heather & Turpin, Etienne, “Art & Death: Lives Between the Fifth Assessment & the Sixth Extinction.” In Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies, edited by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, London: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Grande, John K. “Interview with Edward Burtynsky.” Perspecta 41 (2008): 72-73,

153-159.

Greenblatt, Stephen. “Resonance and Wonder.” In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, edited by Ivan Karp and Steven Levine, 42-56. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 1991.

Gunning, Tom. “What’s the Point of an Index? Or, Faking Photographs”. NORDICOM

Review, edited by Ulla Carlson, 39-50. Göteborg University, 2004.

Jussim, Estelle and Elizabeth Lindquist-Cock. Landscape as Photograph. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Meinig, D. W.. “The Beholding Eye.” In Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes, edited by D. W. Meinig, 33-48. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Mitchell, W. J. T. “Imperial Landscape.” In Landscape and Power, 2nd ed., edited by W. J. T. Mitchell, 5-34. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Morton, Timothy. “Peak Nature,” Adbusters, January 2012.

Stilgoe, John. Landscape and Images. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005.

Weston, Edward. “Seeing Photographically.” In Classic Essays on Photography, edited by Alan Trachtenberg, 169-175. New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980.

Zuromskis, Catherine. “Petroaesthetics and Landscape Photography: New Topographics, Edward Burtynsky, and the Culture of Peak Oil.” In Oil Culture, edited by Ross Barrett, 289-308. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Curatorial Team

Ashley Williams, Hampshire College

Elizabeth Beaudoin Gouin, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Ethan Spielman, Purchase College, State University of New York

Jake Edwards, Hampshire College

Svetlana Zwetkof, Mount Holyoke College

“Sometimes landscapes are not always what they seem.”

“More accordions than a polka ensemble”