Short Term Memory Limits

Have you ever heard that adults can remember about seven pieces of information (like random words or digits) at once? In the past few years, researchers have found that the limit is actually closer to three or four, but that we have an amazing capacity for grouping information so that we can remember more. Think, for instance, of how we tend to remember phone numbers: we break them into “chunks” of three and four digits and remember those groups.

It turns out that infants are very skilled at chunking information as well, but their memories are more limited than adults’.

In these studies, we are interested in infants’ ability to keep track of hidden objects, particularly by “chunking”. By only a few months of age, infants already know that “out of sight” doesn’t mean “out of mind.” For example, after seeing an object hidden by a cloth, infants will expect that removing the cloth should reveal the object. We are interested in how this ability develops and what its limits are. How many hidden objects can babies keep track of at a time? Do infants remember properties of the hidden objects, such as their color or shape? How does knowing the words for an object influence infants’ memory for that object once it is hidden? These are just some of the questions we seek to answer with the present series of studies.

How do you measure all this?

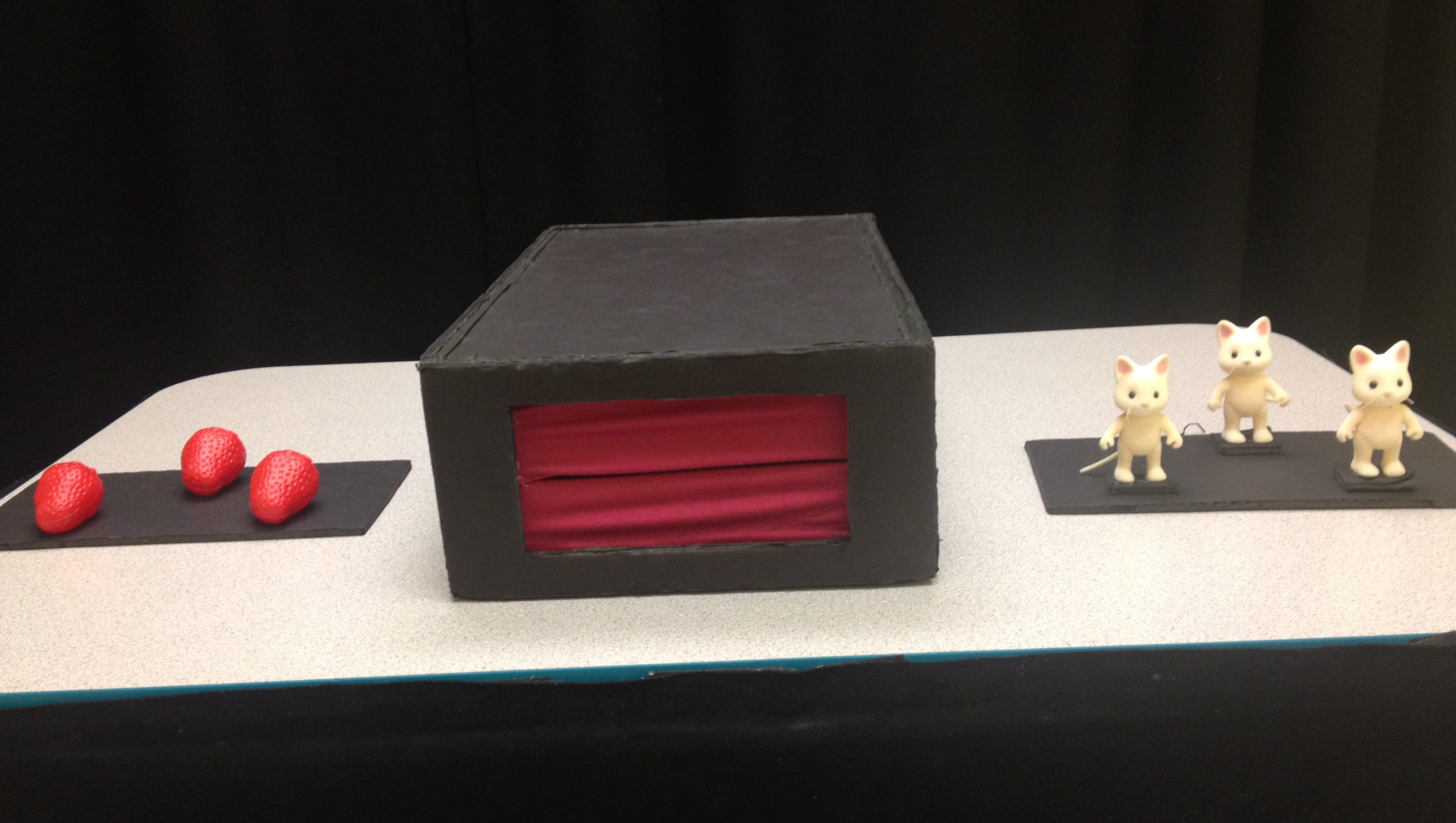

These studies take the form of a simple hide-and-seek game. We will show your baby a group of toys, and then hide them inside a box. Your baby’s task is to reach in and retrieve the toys. On some trials, all of the toys come out of the box, but for some trials, the experimenter will secretly remove some toys from the box, or will swap some out for others. We will then measure when and for how long your baby searches for any remaining objects. If babies tend to search longer when the box is not empty, we can reason that they remember that some toys remain inside.

Objects and Non-Objects

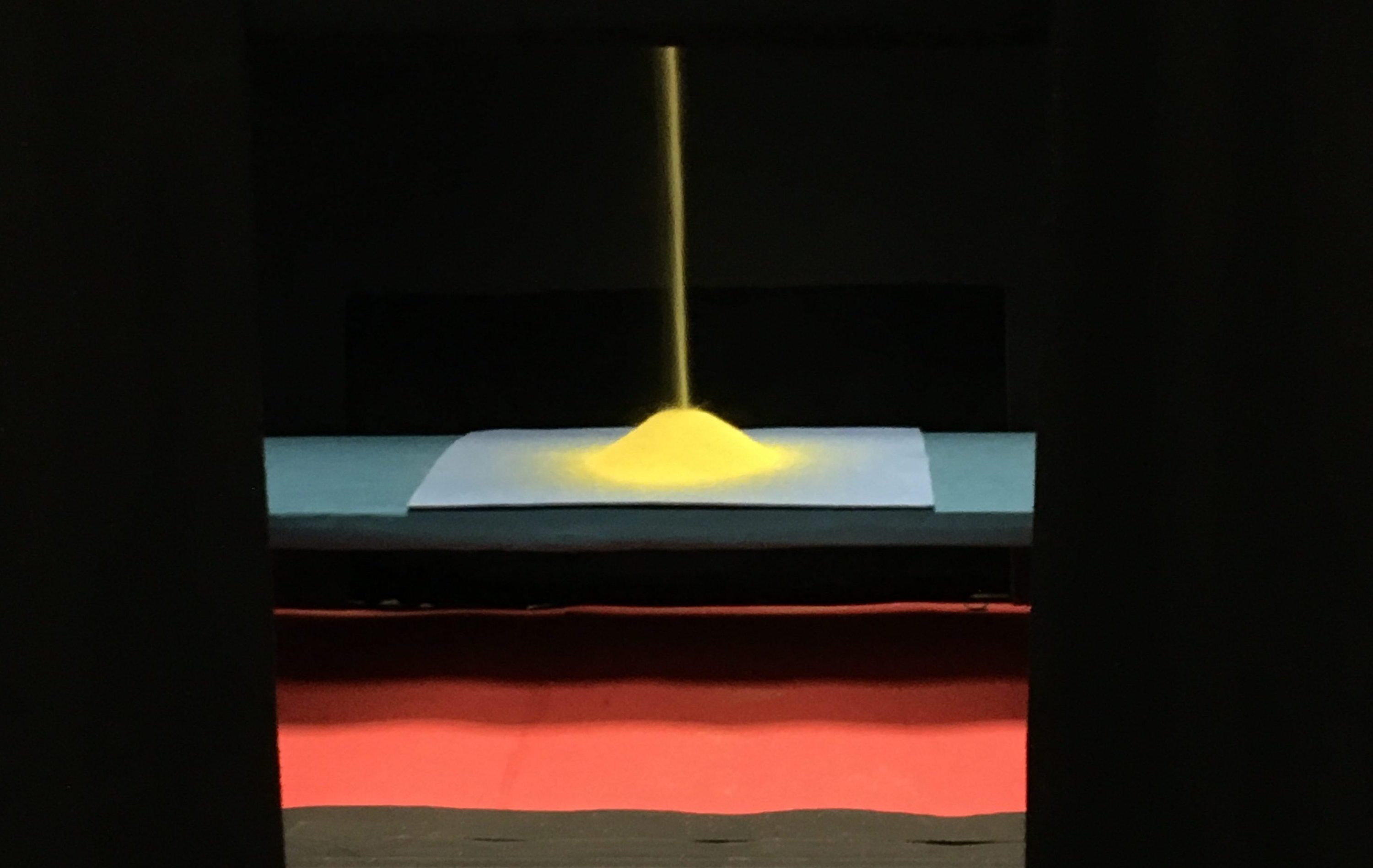

From recent research, we have learned that infants know a lot about how solid objects work and behave. For instance, a baby would not expect a cup to pass through a shelf, or a ball to roll through a wall. However, less is known about how infants think about other substances, like sand.

For these studies, infants sit on their parents’ laps and watch events on a puppet stage. Experimenters show different things on the stage, and sometimes perform little “magic tricks.” For instance, a pile of sand may appear to turn into a solid mound, or a stream of sand may appear to pass through a solid shelf. We want to see if infants notice when these impossible events happen, as an adult would.

How do you measure this?

Infants tend to look longer at events that they find new or surprising. By recording how long they look at different events happening on the stage, we can infer when they were surprised, or noticed that something had changed.

Quantity Comparisons

We know that infants have some abilities to keep track of hidden objects, but what are some of the limits of this memory skill? For instance, how many hidden things can babies keep track of at once? Are they able to remember the difference between two quantities of objects when they are hidden? Does the type of entity (e.g. an individual graham cracker, a pour of Cheerios, or a spoonful of applesauce) affect their ability to track these items? These are just some of the questions we seek to answer with this series of studies.

How do you measure this?

Our “snacky” studies involve hiding a small amount of food (e.g. graham crackers, cheerios, applesauce, or yogurt) in one or two buckets. We know that babies tend to choose a larger amount of food over a smaller amount, so by letting them crawl toward one bucket or another, we can reason about which bucket they think contains more. (It is then up to you if you would like to allow your infant to eat the food afterwards!)