Images are experienced through formats (the newspaper, the scientific journal, the internet meme, etc). In popular media particularly, these formats are encoded with contextual evidences that serve a host of uses. News institutions claim neutrality as truth, photojournalists crop their photographs in attempts to produce objective imagery, while magazines frame perfection as unilateral. Thus, the service of institutions of popular imagery is not to provide objective facts, but rather to create an idealized collective memory through the mass circulation of images; a collective memory that is really based on unburdening the viewer of the violence that a static hegemonic history perpetuates.(1)

Many contemporary artists who deal with institutions of popular media have a different project, but one that pertains to those same institutions. To complicate the objective truths that news and media formats perpetuate is to make visible the formats that have framed the consumption of images. The artists in this group create a hyperaware viewer who is confronted not with the content of popular media, but rather the platforms of manipulation through which they are disseminated.(2)

The newspaper (or news website) exists as one of the most prominent fixture in writing contemporary histories. Both Sarah Charlesworth and Thomas Ruff employ a subtractive appropriative process to make visible how the United State’s national identity is formed. Charlesworth strips textual information away to expose the format that the US experiences ‘the other,’ and through exaggerated pixelation Ruff exposes the flow of information that constitutes national memory. In her work Guerilla Piece (1979), Sarah Charlesworth dissects the formatting of major newspapers‘ coverage of the Nicaraguan civil war over the course of two days (June 4- 5, 1979). Seemingly benign publication choices become hyperpresent as the viewer is forced to contemplate the variety of distinctions, namings, and positions that ultimately skew the United State’s interpretation of war in the ‘Global South.‘(3) The Guerilla fighter becomes an icon of struggle, an illustration of war for a Western audience.

Ruff’s image of the collapsing Twin Towers‘ catches them at the unsure state after the event of impact but before the event of falling. The ambiguity surrounding the actual temporality of the event and the aesthetics of the ruin confuse the media’s construction of collective memory. He poses the questions: How are national memories constructed when only a diminutive percent of the US population witnessed the event? How do networked flows of information construct a singular national identity?(4) And how does the gridded structure of pixelation in this work reflect the structure of image circulation in the United States?(5)

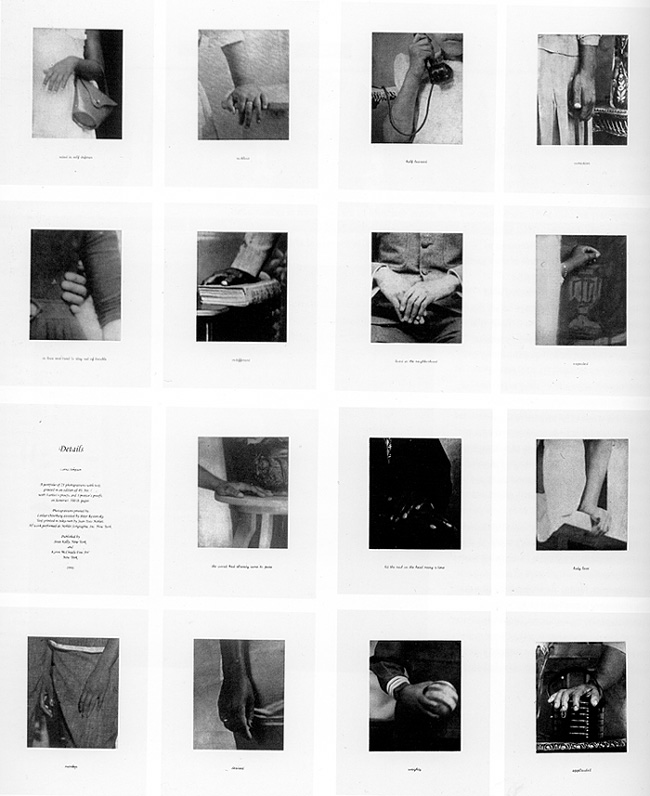

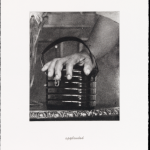

In contrast to Guerilla Piece and jpg ny02 (2004) where artists directly appropriate a source image, Lorna Simpson employs a more structural appropriation. Instead of working with existing images, she reapplies the visual language of anthropological photography and labeling. Her ambivalent labels (“applauded,” “weighty,” “well advised,” etc,) paired with her simple documentary photographs expose the subjectivity involved in naming an image. The individual subjects in her photographs only exist insofar as they are part of her larger project’s structure. The ‘secular humanist‘ approach to human identification is brought into question by subjectifying the history of labeling an image.

Charlesworth, Ruff, and Simpson are complicating the way viewers interact with images. In the digital age the content of an image is easily glanced at, passed over, and forgotten with no deep contemplation. Through the digitization of these artists’ work, the image is made to stand for a larger piece of the whole: that whole being the structures that invisibly guide consumption, influence interpretation, and set in stone histories that are fluid in nature. While these images were made for the museum or gallery, their existence on the internet sheds light on their critique of format. Appropriative intervention renders these structures transparent, their motives undisguised, and their hierarchies disassembled.

Daniel Perlmutter 2014