Maine has areas that are little/medium pop-ups near trash cans near more popular businesses and especially in restaurants that match that of the campus dumpsters, and always in various places when it’s a big event going on or a market pop-up like the weekly flea market or trunk and treat areas. This I’ve seen mostly occurs in Augusta, Portland and more of the touristy type of cities. Towns like Topsham, Lewiston, Brunswick, all of them have smaller versions that vary from place to place. Some weeks it’s the Wendy’s, other times it’s near the Aroma Joe’s, or Starbucks. It’s like a rotation of waste, but the weekends are always the busiest, and dirtiest. Lines go out into the streets, people piling inside the building and demanding orders, I haven’t seen my town on Black Friday or during the discount week, but I am afraid to which is why I will be becoming a hermit again and staying in my designated pie-coma spot. Christmas, trash is stuffed like a kid trying to make it look like they cleaned their room by hiding everything under their bed, summers kick up as well, fall not so much. Depending on the weather, the amount of people, sometimes that waste will be there for days, maybe a week if in a not-so popular area, though I haven’t seen much of that. It’s an interesting hidden, yet not hidden shame, not if you look and a lot of people don’t even if they claim they do.

Category: Waste and the city

Idaho vs. Maine

The highways and freeways of Idaho depending on the areas, are filthy. Trash, tires, broken car bits, dead animals, shoes, bags, a mattress, a toy baby stroller, all interesting things to see on the side of the road. There are signs that say “fine for littering, minimum $200” or somewhat depending on how populated and tourist based the area is. Sometimes Idaho feels like only certain areas stay clean and the rest are free-for-alls that get cleaned up eventually or will be there for a few years and become unspoken land markers. Maine, however, does not tolerate trash on the sides of the road, in fact I’ve seen multiple people pull over and start cleaning trash into bags and then putting them in their cars to take away and dispose somewhere else. Usually, it’s vehicular crashes that takes a bit to get cleaned up, especially the tire bits, but they do get cleaned. I think it’s interesting and speaks about both areas characters.

Mooo-ving Around

Note: Photo will be uploaded later this week, but this idea struck me when I drove by it on the way home and I had to go with it.

Just around the corner from Hampshire, on S Maple St, there are several small farms along the road (2 of them even have ice cream stands!) These farms are mainly occupied by corn stalks and grazing cows – both of which, under human control and consumption, produce quite a bit of waste. We use only the fruit of the corn stalk, and “throw out” the other parts of the plant. To maintain cows, we have a constant cycle of planting, grazing, shitting, repeat. But that’s also what makes this “waste ecosystem” unique in comparison to cities. The waste produced from the corn stalks and cows is put directly back into the cycle to continue sustaining both – extra plant parts become compost, and manure is used as a rich soil. There is very little leftover waste, if any at all – it can all be pumped right back into the system, and without leaving a mark. Well, almost.

Like I mentioned in class the other day, a huge problem I see with waste management in general is the constant moving around that we do with the waste. It seems to reach up to a dozen locations before reaching its final resting place. Evidently, there is concern for the carbon emissions produced from the transporting of the waste. And unfortunately, even the farms are not safe from playing into this game. The distance that the waste will travel on a farm is not much more than a city block (apparently 1 city block = 1.6 acres, cool). But in that small space, the tractors that are transporting the waste are moving at a fraction of the speed of a regular on-road vehicle, and the oil the tractors run on produce tar-black smoke (most tractors use diesel). So, it appears that the farms are still producing plenty of environmentally damaging waste – but due to its state of matter, the physicality of the waste being produced on farms is not immediately noticeable.

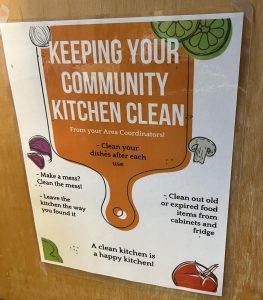

The Merril Kitchen

The Merrill kitchen has a host of waste removal structures, some obvious and some not so obvious. The most waste oriented structure is the black trash can next to the kitchen island and the recycling can by the fire extinguisher. Next is the numerous cleaning supplies that one would normally expect to find in a kitchen, dishwashing soap, paper towels, wipes, a cloth rag hung on one of the ovens, and hand sanitizer and tissue on the window sills. Which I would guess is a preventative measure for Covid/germs, not necessarily physical waste you can see with your eyes. The island houses the oven top which has removable burners to clean underneath and the fan/hood above primary purpose is to suck heat and/or smoke out of the air. Although not conventionally thought of as a cleaning mechanism it operates much in the same way as an air purifier does. Next to the two wall ovens there is a sign on the wall reading “Keeping Your Community Kitchen Clean” and “Make a mess? Clean the mess!” As well as other guidelines that people should be following here. This is notable because people have not been listening to any of the messages on it. The sink has several unwashed pots, silverware, and plates in it. Along with things clearly not being put away with care, instead being left out for somebody else to deal with. On another counter by the entry door people have been piling stuff that seems to be forgotten about. The last time I was using this kitchen was during the beginning of the semester and the fridge then seemed to be a place where food was stored to be eaten. Currently both the freezer and fridge are not a place that seems to be appealing to leave food. The fridge and freezer both stink and the fridge has literal mold growing in it. Both smell more like compost than what they’re supposed to smell like, which is nothing. I think that the leaving of food to the point of rot and willingness to leave the counters littered with cooking objects is because if other people do it then it is ok to do the same, the broken window theory.

Prescott Laundry Room

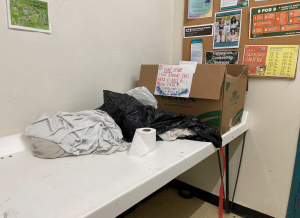

In the Prescott laundry room, there are both formal and informal places where waste collects. The formal ones are a trash can and two small recycling bins by the door to the room. There is also a stack of compost buckets, but it looks like those are meant to be taken to individual mods, not used in the laundry room. The informal waste collection place is a cardboard box and a pile of miscellaneous clothing. The cardboard box has a sign on it that says “DON’T LEAVE STUFF BEHIND. THIS AREA IS NOT A FREE PILE!”. I don’t know why the box is there if people aren’t supposed to put stuff in it but it looks like the box and that corner is being used for unwanted things anyways.

The pile of clothes next to the box is a good example of the broken window theory that was brought up during class last week. Because there is a box and a few things in that corner, there might be less hesitation to add unwanted items to the pile. Clearly, the presence of clothes next to the box is more influential than the sign on the box.

With the informal waste collection place, I think the assumption is that other students will be the ones to take the stuff. If people expected it to be taken care of with the rest of the trash, they would just put it there.

Waste and the city prompt

Choose a place on campus or in the immediate region. Describe how this space is physically structured around waste removal infrastructures, broadly understood. Try to choose a space that isn’t obviously a waste site, like not a local waste transfer station, but one where we wouldn’t normally think of waste. Include photos of the space in your description.

Readings for this week:

Nagle, Robin. Picking up: On the Streets and behind the Trucks with the Sanitation Workers of New York City. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013. Ch 7-9.

Clapp, Jennifer. “The Distancing of Waste: Overconsumption in a Global Economy.” In Confronting Consumption, edited by Thomas Princen, Michael Maniates, and Ken Conca, 155–76. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002.