The East has continually held the fascination of the West, a land reputed in Europe for its exotic culture and sense of the ‘other.’ Historically, the Orient was known as a place of leisure and a welcoming retreat from the civility of Western life. In a contemporary setting, the Middle East is no longer known as some idyllic place, but rather a site of savage and ferocious political struggles. However, both of these ideas are based upon a unique and Orientalist homogenization of culture. It assumes that the Middle East is based upon one cultural standard and ignores regional diversity and variation. Romanticism is an attempt to convey these historical and contemporary motifs to be contrasted and compared with resistance. Here, artists not part of the Middle East create work that reflects a narrative more related to an Orientalist ideal than a veritable depiction of the East. Yet the question must be asked: is a veritable East even possible to attempt? This gallery explores Western depictions of Eastern narrative which commoditize the exotic nature of the foreign and firmly establish a sense of ‘otherness.’

On Romanticism

Nostalgia comes from the Greek ‘nostos,’ meaning to return home, and ‘algos,’ meaning pain. The term was first used in the 17th century to describe suffering from the longing for a home that no longer existed or never existed—a sentiment of loss and displacement as well as a romance with one’s own fantasy. Nostalgia expands beyond the individual consciousness, encompassing not only individual biography but also the biography of groups or nations, existing somewhere between personal and collective memory.1 This link to collective memory provides an explanation for the way memories are created and transferred within sociocultural regions. In this way, nostalgia uses the past to confront issues of the present and advocate for an alternate trajectory for the future, accommodating regressive stances and melancholic attitudes, as well as progressive, even utopian impulses.2 The allure of nostalgia comes from this utopian dimension: the object of nostalgia is a product of the imagination, a notoriously elusive and tantalizing concept that is ultimately unattainable. For the purposes of this exhibition, we will explore nostalgic imagery in the context of romantic nationalism and the ruins of modernity in the Middle East.

By the late 18th century, the presence of revolution and war in France led to the pervasiveness of feelings of anxiety and turmoil throughout Europe. Apprehension toward the trajectory of the future challenged the West’s optimistic faith in reason. It was during this moment of collective agitation that Romanticism emerged. Romanticism praised imagination over reason and emotion over logic. Travelers to the Middle East produced and put into circulation romanticized imagery for consumption by the nostalgic Westerner. Such images were seen to represent a pure, idealized state of harmony and peace to which, someday, Westerners might return.3 The romanticism of nostalgia provided an escape from the then current deficiencies, both real and perceived, as well as a source of restored plenitude and unity. The visual narratives of romantic nostalgia that came out of this period represented the Middle East as a homogenized religio-cultural region. Frederic Edwin Church’s Al Ayn (The Fountain) (1882), shows a largely imagined and romanticized Middle Eastern landscape. The source of light within the painting draws the viewer’s eye to spires and domes of a Middle Eastern mosque in the distance. The painting contains a great deal of imagery, such as the sarcophagus in the foreground and the Rumeli Hisari castle in the middle ground, that conflates the nostalgia felt for ancient Rome with that for the Orient. In the modern era, this form of nostalgic representation continues through emphasis on and consumption of images of otherness and exoticness of the Middle East.

Frederic Edwin Church

Frederic Edwin Church

Al Ayn (The Fountain)

1882

Oil on canvas

60.8013 cm x 92.075 cm

Mead Art Museum at Amherst College AC 1972.109

Gift of Herbert W. Plimpton: The Hollis W. Plimpton (Class of 1915) Memorial Collection

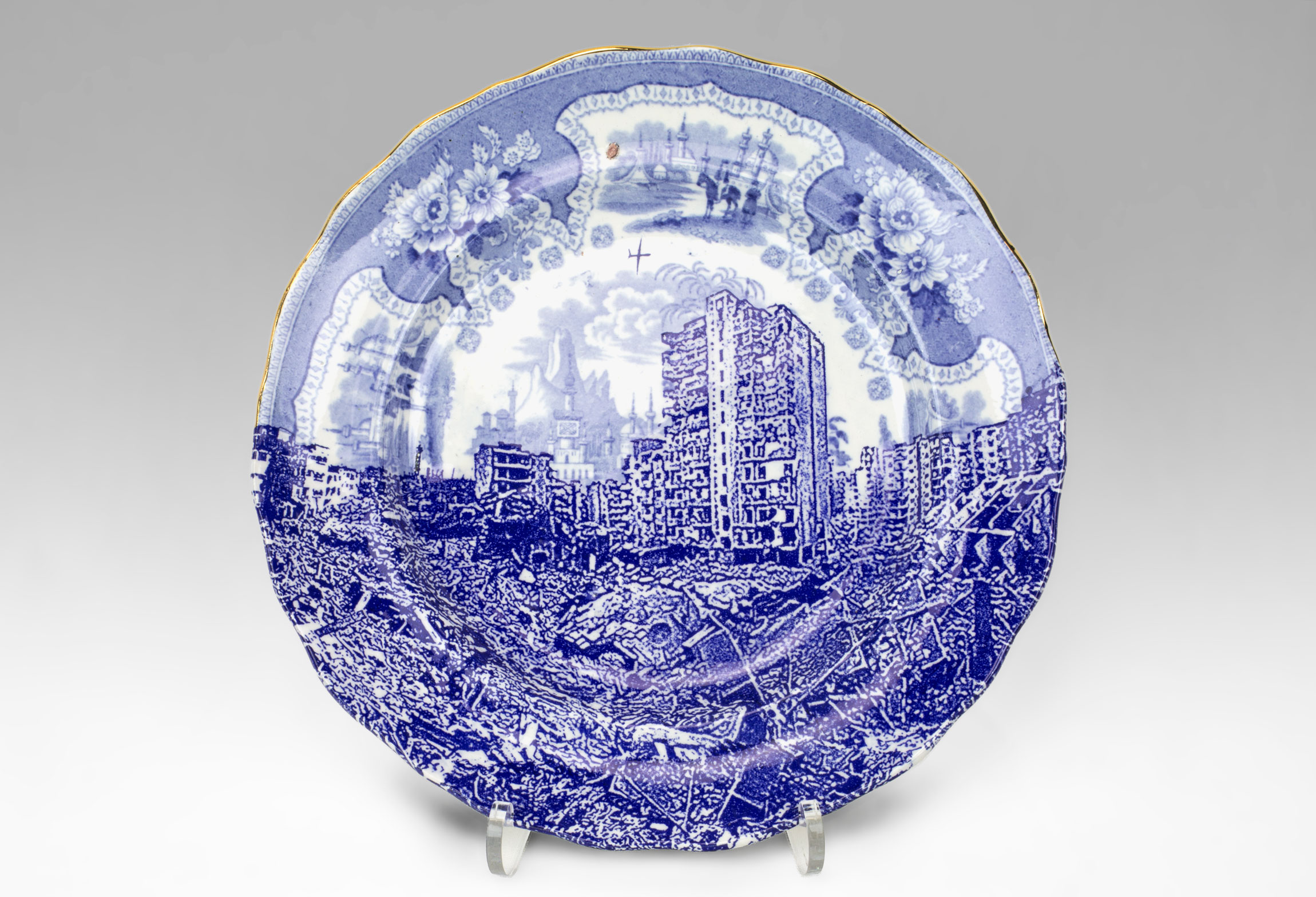

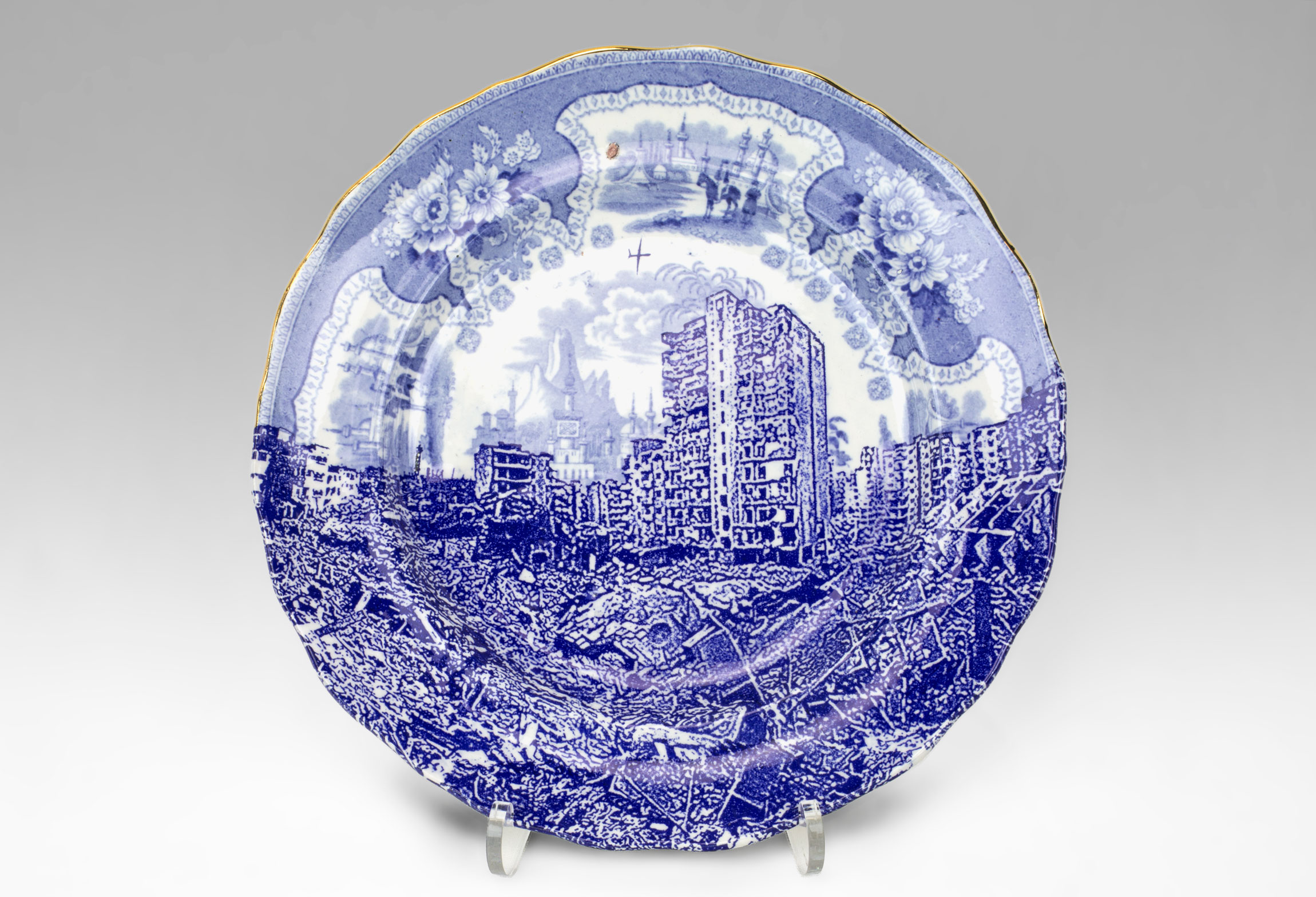

In contrast to the romanticized depiction of the Middle East as a mythical land of plenty, there has been a widespread emergence of imagery in the media that shows the region as a land of destruction and ruin. This depiction speaks to a different romantic narrative, harkening back to the ruins of classical antiquity and the loss of the time and culture from which they came. In contemporary images of destruction in the Middle East, the rubble is transformed and aestheticized into a modern representation of the nostalgic ruin. The pervasiveness of such imagery in the media illustrates a strange obsession with ruins that has developed in the West as part of a broader discourse about memory and trauma, genocide and war. 4 Depictions of the ruin instill in the viewer a sense of sympathy for the destruction of a culture, as well as a hope to reclaim the past in order to construct alternate futures. In Paul Scott’s Scott’s Cumbrian Blue(s), Palestine, Gaza (ca. 1840; 2015), Scott has superimposed an image of destruction in the Middle East on a blue and white transferware plate. This image of destruction was taken from the media and used by the artist to represent the political climate of a nation. The media’s propagation of selective images of the ruin consequently perpetuates otherness, limits social memory, and constructs homogenous narratives of the Middle East.

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

Scott’s Cumbrian Blue(s), Palestine, Gaza

ca. 1840; 2015

Sculpture, Refined earthenware, lacquer, and gold (kintsugi); transfer printed with cobalt blue and lead glaze (pearlware)

Overall: 30.5 cm

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum MH 2015.12.2

Purchase with the Elizabeth Peirce Allyn (Class of 1951) Fund

-Lauren Thompson

Notes:

1. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2008), XVI.

2. Michael Pickering and Emily Keightley, “The Modalities of Nostagia,” in Current Sociology, Vol. 54(6) (2006), 919.

3. Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, Cultural Absolutism and the Nostalgia for Community (Waterloo: Political Science Faculty Publications, 1993), 326.

4. Andreas Huyssen, “Nostalgia for Ruins,” Grey Room, No. 23 (2006), 7.

European interpretation of the Middle East has shaped both modern and historical understanding of the latter’s culture and practice. Frederick Garber explains the relationship between Europe and its perceived notions of the ‘East’ as such: “The Oriental is a version of that which stands over against us and, by virtue of its unlikeness, helps us to understand what we are in ourselves. It is a curious mirror, a magic one in which, by staring at Otherness, we come to see ourselves more clearly.”1 This Orientalist vein of thought creates the idea of the voyeur as one who looks within the mirror that Garber describes. The voyeur examines orientalist objects created for Western consumption and attempts to define their own role through such commoditized objects.

As European interest in the Middle East was predominantly based upon trade and tourism, artists created exotic interpretations of their travels which served a twofold purpose: to pander a cultural movement which demanded Orientalist motifs and create easily sellable work; and, to serve the personal motive of identity such as the one Garber references. By capturing an image of the Middle East to create a physical, handheld version, the subject transformed into an easily possessed and examined object. The voyeur could then, at any time, examine their captured image of the Middle East, isolated from all other information and truth, and draw their own conclusions on the status of the East and, by unconscious extension, the West.

Eugène Delacroix

Algérienne

n.d.

Oil on canvas

24.4475 cm x 19.05 cm

Smith College Museum of Art SC 1921:11-1

Gift of Colonel Walter Scott

In the nineteenth century, the Middle East was renowned as a place of leisure for Western travelers seeking asylum from the civility of everyday life, as well a popular destination for those on the Grand Tour. Even the popular Impressionist artist, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, vacationed in Algiers. In doing so, he wished to learn the style of the Orientalist painter, Eugène Delacroix, whose work primarily features scenes of the romanticized Middle East.2 Delacroix’s images promote the idea of the voyeur through many of his popular harem scenes. As a place forbidden to men, the harem garnered much interest to male travelers, anxious to known the erotic secrets that would be found within. Such that the French critic, Theophile Gautier, once stated, “Only women should to go Turkey – what can a man see in this jealous country.”3 During this time, laws of propriety required women to wear veils while in public, which served to only increase artistic demand for the unveiled Arabic woman.4 Because of this, lower class Jewish women from the local populace were often found to pose as models instead, or European women would don Eastern costume to finish the drawing upon the artist’s return. The resulting image, while exotic and foreign, is carefully composed with Oriental motifs.

The Oriental voyeur is a role best described in terms of identity, a social construct revealed by popular culture, as the romantic motifs found within European depictions of the Middle East reveal much more of European society than that of its conceived Orient.

-Amanda N. Bolin

Notes:

1. Frederick Garber, “Beckford, Delacroix and Byronic Orientalism” in Comparative Literature Studies 18, no. 3 (1981), 323

2. Roger Benjamin, Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa, 1880-1930 , (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 36

3. Reina Lewis, “‘Only women should go to Turkey’ Henriette Browne and Women’s Orientalism” inThird Text 7, no. 22 (1993,: 57.

4. Benjamin, 43.

Orientalism fluctuates with the ebbs and flows of Middle Eastern and Western relations, but it never disappears. When Western artists depict the East, certain imaginaries will always be perpetuated. One element of nineteenth century Orientalism that continues into the present is the fetishized image of the ruin. Depictions of bombed-out buildings and abandoned spaces represent a continuation of this obsession with the ruin in the present. Because Western media continues to broadcast images of ruined spaces in the Middle East, wrecked structures begin to serve as an analogy for oppression in the region. In works by artists Paul Scott and Lauren Greenfield, ruined or abandoned structures are emblematic of out-of-context Middle Eastern oppression.

This is no accident—according to social anthropologist Dag Tuastad, out-of-context violence is the most common image of the Middle East circulated among Western audiences. This, he argues, leads to an assumption that violence is a characteristic of Middle Eastern culture itself. When an oppressed culture is seen as ‘violent,’ this serves as a way of giving power and legitimacy to colonial projects.1 When the media shows destroyed structures as evidence of instability and violence outside of any specific framework, it serves as a means of upholding colonialism. In Paul Scott’s ceramic work Scott’s Cumbrian Blue(s), Palestine, Gaza, he superimposes an image of a destroyed building over an Orientalist landscape of Palestine. The idealized landscape of the blue-ware plate is juxtaposed with abstract destruction. By printing an image of out-of-context violence, and naming it after an entire country, he suggests that hopelessness is a characteristic of Palestine itself, thus falling into Tuastad’s formulation.

Paul Scott

Paul Scott

Scott’s Cumbrian Blue(s), Palestine, Gaza

ca. 1840; 2015

Sculpture, Refined earthenware, lacquer, and gold (kintsugi); transfer printed with cobalt blue and lead glaze (pearlware)

Overall: 30.5 cm

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum MH 2015.12.2

Purchase with the Elizabeth Peirce Allyn (Class of 1951) Fund

There are subtler ways that the contemporary ruin can support hegemonic understandings of Middle Eastern oppression. Photojournalism, probably the field that creates the most widely circulated depictions of the Middle East, perpetuates this idea. While contemporary photojournalists often provide a lot of context with their work about the Middle East, they often photograph abandoned spaces as if they show some sort of evidence. For example, when American photographer Lauren Greenfield visited Dubai in 2009, she took the photograph United Emirate Hills, Dubai. In it, an apocalyptic, lone bird is shown flying above bent steel beams and rubble. The caption provided for the photograph says that property values have declined by “as much as 40 percent” in the Emirates Hills neighborhood. In the background of the photograph, far away from Emirates Hills, skyscrapers of various shapes rise out of the fog. Some of these buildings are where investment banking takes place, since Dubai is a free trade zone for many transnational corporations.2 This photograph juxtaposes the rubble of an economically declining Middle Eastern neighborhood with the soaring structures of late capitalism. One can see a formal connection with Scott’s piece, in which the foreground shows a ruined space while the background shows an idealized landscape.

Lauren Greenfield

Lauren Greenfield

United Emirate Hills, Dubai

2009

Photograph, digital c-print

27.94 cm x 35.56 cm

Smith College Museum of Art SC 2010:5

Gift of Carol T. Christ and Paul Alpers

It is not fair to compare Scott and Greenfield’s artistic practices, however. Greenfield carries out her work with journalistic integrity, providing ample context with her photographs. The full series includes photographs of mansions, malls, tropical landscapes, and the expats who visit them. She creates images of the workers in the Solapur labor camp outside Dubai and notes in the caption that “they had not been paid in seven months.”3 Greenfield thus photographs the two sides of the coin—both the idealized landscape of wealth as well as the exploited labor used to support it. Greenfield shows a balanced depiction of a particular part of Dubai. What she does not do, however, is show the more nuanced, less dramatic view of the city. As editor Deepak Unnikrishnan writes in the introduction to a publication featuring Dubai residents, “most narratives of Dubai focus on its extremes—solar-sintered skyscrapers made from sun, sand and glass or the unknown laborers that built them.”4 Greenfield uses this juxtaposition of architecture in United Emirate Hills, Dubai, to highlight these two extremes. While this technique constructs a successful narrative, one must be aware that it is just one narrative about the city among many that could be told. Greenfield herself seems aware that this is a constructed narrative—in an interview with the New York Times, Greenfield states that she would call the story of Dubai “an improbable fairy tale… anything that could be fantasized could be built.”5 Greenfield uses the ruined structure as a correlative to the boundless skyscrapers of transnational finance. While the ruin sometimes serves as evidence of oppression or failure, one must understand that this is just a narrative. Extremes cannot be relied upon in a time when the popular media portrays the Middle East as a place of extremes and nothing but extremes.

-Nolan Boomer

Notes:

1. Dag Tuastad, “Neo-Orientalist and the New Barbarism Thesis: Aspects of Symbolic Violence in the Middle East Conflict(s)” in Third World Quarterly, 2003, 591.

2. Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (Brooklyn: Verso, 2014), 26.

3. James Estrin, “Showcase: Dubai’s Improbable Tale” in The New York Times (New York, NY), 30 November 2009.

4. Deepak Unnikrishnan, “Editors’ Note” in The State Vol IV: Dubai, (The State: 2013). See also Nezar Alsayyad, Consuming Tradition, Manufacturing Heritage: Global Norms and Urban Forms in the Age of Tourism (London: Routledge, 2013) and Bryan S. Turner, Orientalism, Postmodernism and Globalism (London: Routledge, 2002).

5. Estrin 2009.