Today the word resistance often has negative connotations and is associated with political action, especially regarding the Middle Eastern region. However, this exhibition attempts to reclaim the idea of resistance and show that it can encompass several different forms of action, including something as simple as providing moments of normalcy in difficult situations. In essence, Reorient focuses on how resistance can be defined as speaking back to the Occident and its homogenizing discourse surrounding the Middle East. By addressing issues such as artists who resist identity labels, acts of powerful domesticity, self-depictions through the medium of photography, and the importance of personal choice in a globalizing world, we weave together several different narratives of resilience in an effort to convey the varied and individualized nature of resisting Orientalism.

On Resistance

Tourism and photography might be thought of as the handmaidens of Orientalism. During the last half of the 19th century, photographers from the West visited the Middle East to make and distribute millions of photographic images.1 A well-known tourist photographer was Francis Frith, who left England three times between 1856 and 1860 to photograph the Middle East. While he photographed monuments almost exclusively, Frontispiece: Portrait of Turkish Summer Costume represents a notable exception. This self-portrait of Frith was taken in 1857 for the preface of his book “Egypt and Palestine.” He calmly looks straight into the camera, wearing an ornate blouse, Turkish carpet slippers, and a fez. According to art historian Gordon Baldwin, this photograph fits into a tradition of Western artists like Rembrandt creating self-portraits in exotic clothing. Frith titled this image Turkish Summer Costume even though he never actually traveled to Turkey. Because he frequently travelled to Egypt, which along with Turkey was part of the Ottoman Empire, he may not have cared to distinguish between the two.2

Francis Frith

Frontispiece: Portrait of Turkish Summer Costume

1858

Photograph, albumen print photograph on mount

22.86 cm x 15.875 cm

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum MH 1982.10.1.1

Gift of Susan B. Matheson (Class of 1968)

Problems arise because photography during this early period was considered an accurate and objective way of communicating visual information.3 Photographs about the Middle East, like Frith’s ‘Turkish’ photograph, would often travel either with inaccurate captions, or no captions at all, suggesting that the photographs were meant to speak on their own. Photography during this period was also deeply affected by trends in Orientalist painting, a medium that was traditionally meant to delight rather than to instruct. When photographic images were created as pleasing depictions of a foreign locale for Western viewers to enjoy at home, photography failed to impart objective information about the Middle East. In fact, the photographic process used by most tourist photographers during this period was called ‘calotype,’4 the etymology of which is made up of the Greek words for ‘beautiful’ and ‘impression.’ While beauty and veracity are not in fact opposites, it cannot be ignored that the expression of beauty was emphasized over the articulation of objective information during this period.

Abdullah Frères

Abdullah Frères

Les Étudiants d’El-Azhur (Université Arabe)

19th century

Albumen Print

20.48 cm x 26.04 cm

Minneapolis Institute of Art 82.57.3

Gift of Charles Herman

When the technology of photography became available to Middle Eastern photographers in the 1850s, they began to change how their own people were photographed. While early Western photographers were still recreating themes already present in Orientalist painting, local photographers were able to depict Middle Easterners “in their natural environments, working, socializing, picnicking, posing in elegant clothes with their children and retainers, and exuding a sense of dignity.”5 This appears in the photograph Les Étudiants d’El-Azhur (Universite Arabe), created by the photography studio Abdullah Frères, run by three Armenian brothers. While no date is provided with the photograph, it was most likely taken in 1886 or a few years after, when the brothers opened a branch of their firm in Cairo. This photograph shows a quotidian and empowering scene of Egyptian students taking a break from their university classes, rather than an exoticized depiction.

-Nolan Boomer

Notes:

1. Paul E. Chevedden, “Making Light of Everything,” in Middle East Studies Association Bulletin (1984), 151.

2. Gordon Baldwin, Roger Fenton: Pasha and Bayadere, (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1996), 55-56.

3. Chevedden, “Making Light of Everything,” 151.

4. Francis Frith is a notable exception—rather than using a calotype process, he utilized a wet-collodion process which was less common but easier to use in dusty desert conditions.

5. Rana Kabbani, “Regarding Orientalist Painting Today,” in The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting, ed. Nicholas Tromans (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 44.

The act of resistance in the domestic sphere is a phenomenon that is often overlooked, especially under the clouded overlay of Orientalist thought. The concept of separate spheres arose with the ancient Greeks but found prominence during Britain’s Victorian Era. The concept purported that a women’s place was in the domestic sphere while the man’s was in the public sphere. The gendered politics of this era coincided with the Industrial Revolution, and by the end of the 19th century the spheres of home and public—or work—were separate. However, women did succeed in challenging these gendered ideals, and many were able to break into occupations predominantly filled by men. Regardless, middle class women worked diligently to maintain the home by raising families and overseeing maintenance.1 Can this act of maintaining the home, or the domestic, be argued to be an act of resistance and resilience? Arguably, sustaining the home and family are essential in order for life to continue and to thrive. Additionally, many artistic forms associated with the domestic, such as embroidery, also function as daily acts of resistance and resilience. This can be clearly seen in works produced in the Middle East, where these art forms speak back to several Orientalist notions concerning women and domesticity.

Large portions of the Middle East in the 19th century were under Ottoman rule, and arguably the concept of separate spheres was not as prominent or delineated as in Victorian Britain. For example, focusing on embroidery, a tradition that has carried through to present day, “both men and women, also in North Africa and the Middle East, carry out embroidery at a professional and domestic level.”2 According to Vogelsang-Eastwood, “in general, women tend to produce embroidery at home for domestic use or for sale locally” and “men manufacture items on a public level.”3 People of all religions and classes historically practiced the art of embroidery in the Middle East, and the majority continues to do so today, as the art form has been passed down through generations. This longstanding tradition of embroidery also included opportunities for schooling, especially for women, as the photo of the Arab School of Embroidery in Algiers depicts. The Maghreb, a region of North Africa, was especially known for having these special embroidery schools, where young girls learned the art from female teachers. Additionally, throughout the Maghreb, women are carrying out embroidery at an increasingly professional level as well as a domestic level.4

Detroit Photographic Co.

Detroit Photographic Co.

“Arab School of Embroidery, Algiers, Algeria” from Views of people and sites in Algeria in the Photocrom print collection

ca. 1899

Photocrom color print

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC Lot 13420, no.043

The art of embroidery in the Middle East is practiced across gender, ethnic, religious, and class lines, while simultaneously blurring the idea of domesticity. This transcendent art resists Orientalist notions that Middle Eastern women are relegated to a domestic sphere where they live quietly and simply take care of the family. Instead, in examining the practice of embroidery, something generally considered as a simple, domestic, feminine practice, one can see that it is in fact a highly respected art form. Embroidery allows both men and women to make a living, provides historical and generational familial connections, and resists notions of the docile domestic sphere. In essence, transforming a ‘domestic’ act into an act of everyday resistance and resilience in the face of pervasive Orientalist rhetoric.

-Camille Reynolds

Notes:

1. Jan Marsh, “Gender Ideology and Separate Spheres in the 19th Century,” Victoria and Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/g/gender-ideology-and-separate-spheres-19th-century/

2. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, Encyclopedia of Embroidery from the Arab World, (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016), 11.

3. Ibid.

4. Claire Nicholas, “Moroccan Women Embroiderers: Technical and Ethical Reconfigurations,” in Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology 49, no 2 (2010), 106.

In this section I will focus on Diana Al-Hadid’s work We Will Control the Vertical (2009), arguing that the work is not focused on representation, and can be understood using post-identity scholarship. Al-Hadid’s work is not recognizably political in its subject matter—she has stated that her interest is in materiality and form, as well as in commenting on aspects of the human condition.1 These interests are embodied by her work and can allow for a political reading. The art world has historically been interested in non-Western artists when they offer a cultural representation that is different from Western epistemologies and understandings, while Western artists were allowed to comment on personal experience and human condition. As Kobena Mercer states in his essay titled “Black Art and the Burden of Representation”:

When artists are positioned on the margins of the institutional spaces of cultural production, they are burdened with the impossible task of speaking as “representatives” in that they are widely expected to “speak for” the marginalized communities from which they come.2

Other scholars have tried to broaden representational readings. Thelma Golden’s seminal Freestyle exhibition at The Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001 argued for post-black understandings of Black American art. By post-black Golden was advocating for a reception of Black art that was not limited to a commentary on core Black experience, since there is no core experience outside of the unique and individual experiences of Black Americans.3 Many scholars, artists, and public figures have adopted post-identity and post-ethnic understandings of art. 4

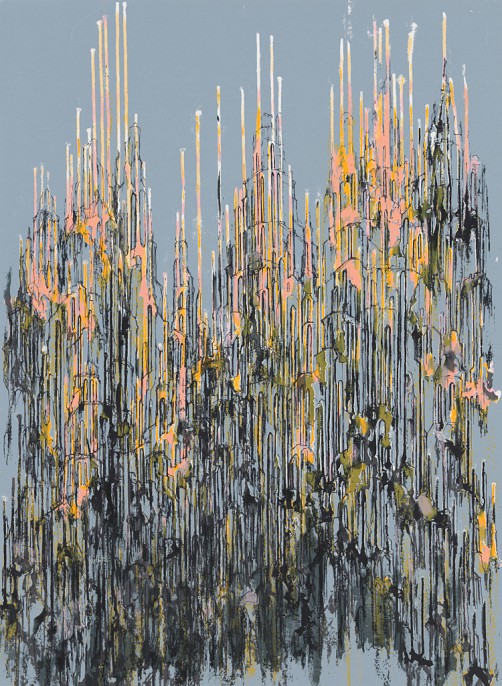

Diana Al-Hadid

We Will Control the Vertical

2009

8 color screen print on Coventry Rag 335 gsm

76.2 cm x 55.9 cm x 2.5 cm

University Museum of Contemporary Art at UMASS Amherst UM 2012.6.6.1

Given by Exit Art

What Al-Hadid does in her practice can be understood within the discourses of post-identity in that she does not strive in her work to explain a Syrian American experience or Syrian American identity, but rather her thoughts as an individual, regardless of whether the artist feels that their work is informed by their racial, ethnic, or cultural identity or not. As she explained in an interview with Art21: “I don’t make work because I’m interested in something and I want to explain it to you. I’m making it to become interested.” 5 Drawing on material and experimenting with form, Al-Hadid creates unique, often architectural, forms to try to understand something about the human mind. Paintings such as this one challenge the idea that representation has to be tied to identity or experience. In politicizing the way in which we understand Al-Hadid’s work, I am advocating for a non-political view of her subject matter. In doing so, I am making an effort to call into question the way in which we view Middle Eastern art, advocating for nuanced readings that are willing to go through or beyond identity.

-Theresa Mitchell

Notes:

1. Steven Litt, “The Akron Art Museum salutes Diana Al-Hadid, a Kent State grad in search of art world success – on her own terms.” November 27, 2013. The Plain Dealer. http://www.cleveland.com/arts/index.ssf/2013/11/the_akron_art_museum_salutes_d.html

2. Kobena Mercer, “Black Art and the Burden of Representation” in Welcome to the jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (New York: Routledge, 1994), 235.

3. Derek Conrad Murray, “Mickalene Thomas: Afro-Kitsch and the Queering of Blackness” in American Art 28, no. 1 (2014), 9-15.

4. For more scholarship on identity and post-identity in art see Hamid Keshmirsheka, “The Question of Identity vis-à-vis Exoticism in Contemporary Iranian Art” in Iranian Studies 43, no. 4 (2010), 489-512; Sara Angel Guerrero-Rippberger, “Panethnicity, Postidentity, and Artist Groups in Latin America and the Middle East, 2003-2010” in Source: Notes in the History of Art 31, no. 3 (2012), 53-63; Soraya Murray and Derek Conrad Murray, “On Art and Contamination: Performing Authenticity in Global Art Practices” in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 22, no. 1 (2008), 88-93; and Jessica L., and Cherise Smith, “The Particulars of Postidentity” in American Art 28, no. 1 (2014), 2-8.

5. Art 21. “Diana Al-Hadid’s Suspended Reality | ART21 “New York Close Up”. Youtube video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zaiF27LLDkQ.