TEXTILES & POWER

Power must be viewed in part as an artifact of imagination and a facet of human creativity

-W. Arens and Ivan Karp

-W. Arens and Ivan Karp

Systems of power operate in every society, and all power structures require signs to articulate relationships between people. People have used textiles to represent power in diverse cultures throughout history. The following examples demonstrate various ways that textiles have served as tools to uphold, challenge, reshape, or gain power.

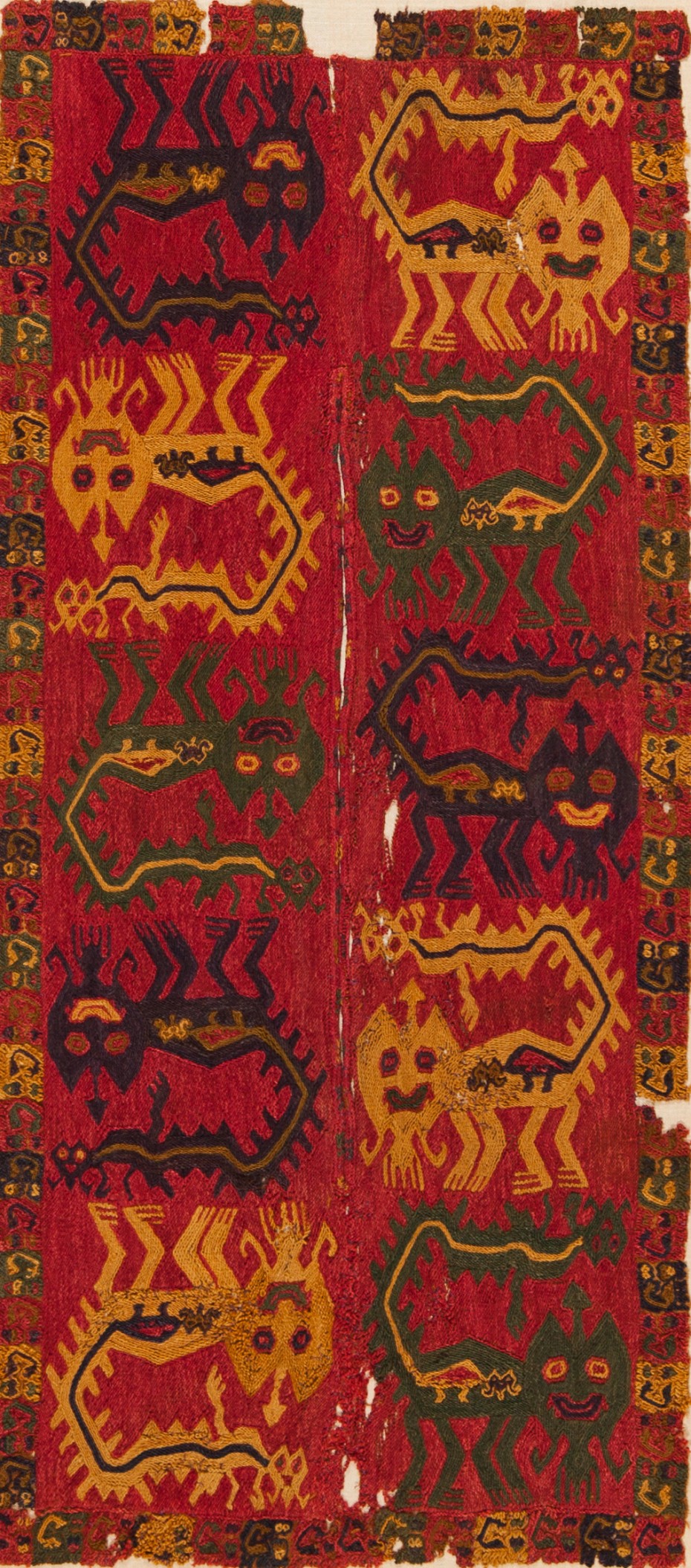

Many of the textiles that are attributed to the Paracas culture were found in the Necropolis burial site in the Nazca Desert, Peru. Each person buried there was wrapped up within a bundle of intricately embroidered cloth, much like the Mead’s Clothing fragment with Pampas Cats. The range of mummy bundles within the burial site suggests status differentiation, since some bundles contain more garments of a higher quality. The diversity of motifs on each cloth suggests that these garments were commissioned in order to inform others of about the wearer’s social position. The elaborately woven and hand-embroidered textiles demonstrate how textiles were used within the Paracas culture to uphold systems of power that were already in place.

Peru, Paracas, Clothing fragment with Pampas Cats, ca. 100 B.C.E.-100 C.E.

The grandiose Flemish tapestry Leopard Hunting Scene depicts more than just an imaginative game hunt. In fact, it uncovers narratives about Europe’s fear of and fascination with “the Orient” in the 17th century. Although trade between Europe and the Middle East was prosperous, tensions between the regions grew. Depictions of hunts of non-native game and struggles against Ottoman forces became popular subjects in painting and other decorative arts at this time. The imagery on this tapestry displays a band of European hunters tracking down a leopard, an animal native to the Middle East. The hunting troop echoes European efforts to challenge the rising powers of the Ottoman and Persian Empires.

Flemish, Tapestry with Leopard Hunting Scene, 17th c.

The Yoruba culture, situated most densely in present-day Nigeria, has a strong tradition of resist-dyed (eleko), indigo textiles called adire. Centuries old, the tradition carried on unflinchingly under British colonial rule. The Oloba Adire Eleko, a design made through stenciled wax resist, reveals changing power structures over almost a century in Nigeria. Originally, this piece was made to commemorate King George V and Queen Mary’s Silver Jubilee in 1935. The combination of the subject matter, a celebration of Britain’s King and Queen, with Yoruba textile traditions places this piece in a specific cultural moment of 19th century European imperialism. However, soon after it was made, Nigerian nationalist movements began to materialize. As the Nigerian people began to protest colonial rule, this textile took on new meanings. As the original stencils were traced and replaced, the design became less about the British and more about the Yoruba people. English words were replaced by Yoruba proverbs, and the images of the King and Queen were no longer in their likenesses. Today, the two figures in the center represent Adam and Eve, not former colonial rulers. As power structures were reshaped in Nigeria, so were the textiles representing them.

Nigeria, Yoruba, Oloba, adire eleko, 20th c.

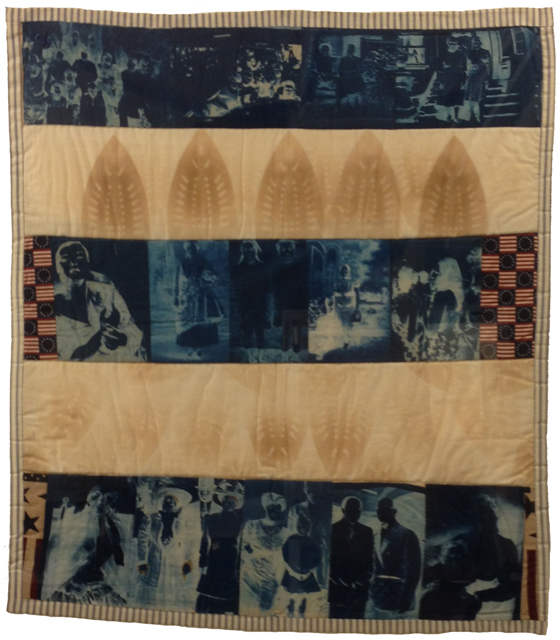

Artist Amalia Amaki challenges racist power structures in the United States by locating the black experience in American culture. She frequently uses fabric as a medium. In her piece Three Cheers for the Red, White & Blue #15, she juxtaposes patriotic imagery with cyanotype portraits of black Americans, which include portraits of enslaved Africans, blues singers, and her own maternal aunts. Her patchwork alludes to African American quilt traditions, and metaphorically, she stitches black culture back into the dominant narrative of the United States. Furthermore, the work evokes cotton and indigo, which were among the most important commodities in the trans-Atlantic slave trade between the Americas and West Africa. Amaki reframes and reclaims these materials while honoring the contributions of African Americans to American culture in an effort to upend contemporary systems of power with deep historical roots.

Amalia Amaki (American, 1959-), Three Cheers for the Red, White & Blue #15, 1995

Textiles and systems of power are fabricated in every society. When brought together they transmit messages that dismantle, uphold or establish the status quo. The cultural signifiers stitched into the textiles reveal the underlying power structures at play.