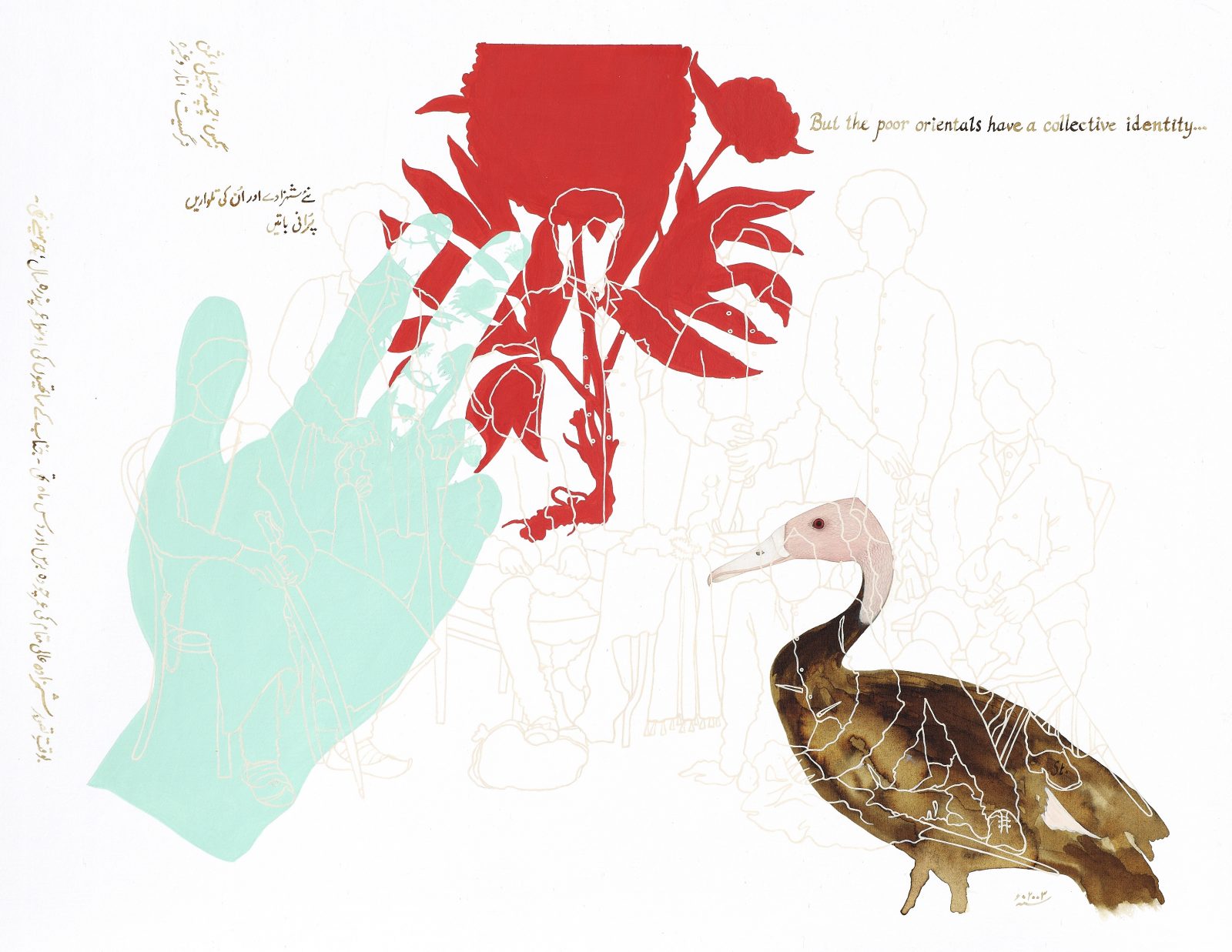

It is often claimed that the power of visual representation lies in its ability to communicate across geographical and linguistic barriers. However, the complexities of cultural difference often result in misinterpretations and misrepresentations. The image plays an active role in constructing collective narratives as the increasingly significant form of 21st century communication. Trapped in a complex system of culture, power, and access, images complicate the telling of the story.

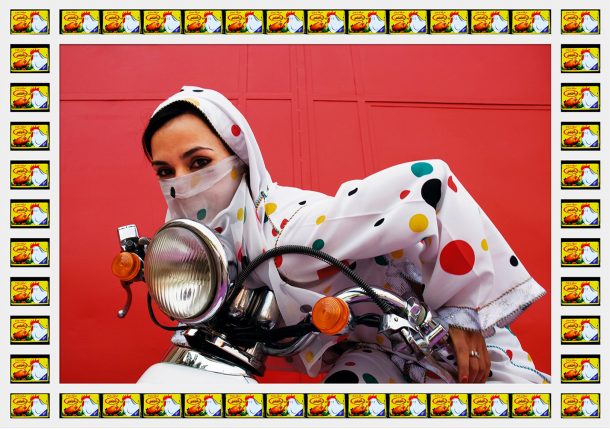

This exhibition explores the wide gaps that continue to exist between popular narratives of the Middle East and the realities of intricately nuanced cultures. From painting to photography, this exhibit examines the romanticized vision that colors historic and contemporary representations of the Middle East and traces the ways in which generalizations, fabrications, and stereotypes continue to widen the distance between two hemispheres.

Reorient investigates the power of representation by contrasting these images with narratives of individuals that confront adversity through resistance and resilience. These range from artworks by Middle Eastern artists who defy labels to depictions of individuals trying to carve out moments of normalcy despite the flux and chaos of their environment. By creating a dialectic between Resistance and Romanticism, this exhibit questions whether the search for a veritable East is Orientalist in and of itself.