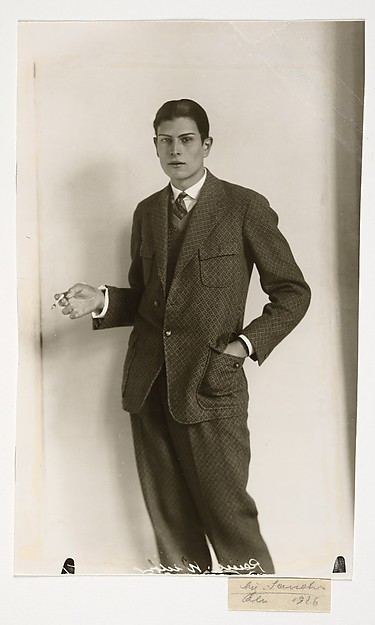

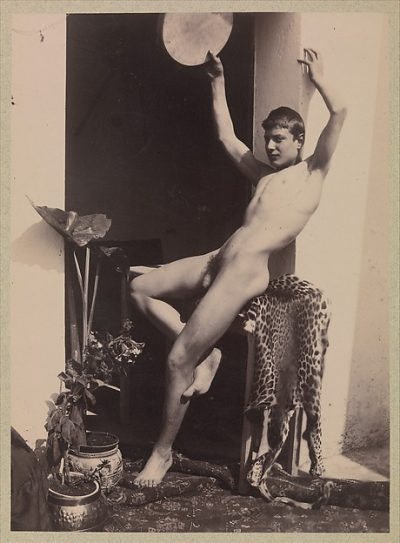

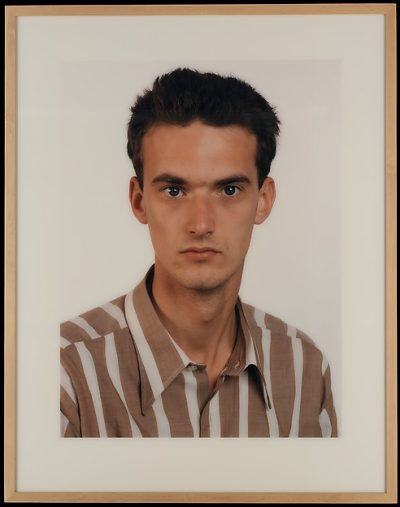

The student portrait constitutes a specific genre of photography, like the baby snapshot, the author photo, or the mug shot. In fact, the student portrait bears an inverse relationship to the bureaucracy of the mug shot by capturing a person’s entrance into the public sphere, only instead of ascribing criminality to its subject, it delivers the individual into educated society. The image severs the distinction between public and private life, incorporating elements of a personal intellectual or artistic endeavor and of the (often young) subject’s professional emergence. As a visual marker of academic citizenship, the student portrait allows the viewer to access the histories of photography and education, side by side.

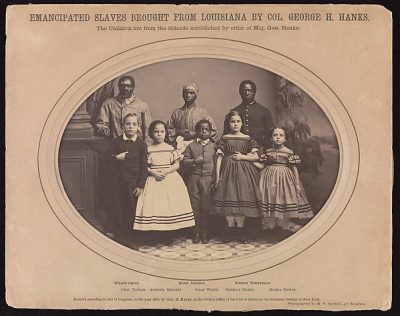

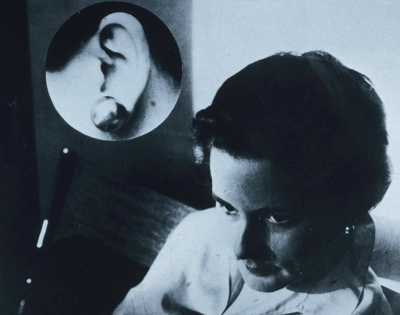

Photography came to fruition in the modern era, a period marked by changing technology, culture, and politics. It also shaped modernity in the cultural imaginary through the production of images: think of photographs of early modern architecture, scientific and medical discoveries (and abuses), and the “genre of portraiture as a bourgeois inheritance” 1—a manifestation of the possessive individualism (and all its contradictions) 2 that constituted the ideal modern subject. From its inception, photography has been bound to systems of education and has always had a relationship with text, whether illustrating it or replacing it. And the encyclopedic methods and documentary impulse of many early photographers pointed to the rise of visual culture as a dominant form of information, echoed by László Maholy-Nagy in his premonition that “those who are ignorant in matters of photography will be the illiterates of tomorrow.” 3

What do student portraits articulate about the relationship between photography and education? A preliminary response is that scholarship, the production of a theoretical discourse on photography, lends the work much of its meaning and value as a fine art. But more broadly, the connections between students and photographs are as variable as they are between students and educational institutions. For some students, a portrait takes place at the cusp of their academic achievement and professional success. For others, the portrait is inflected with histories of oppression, forced assimilation, and uneven distribution of opportunity.

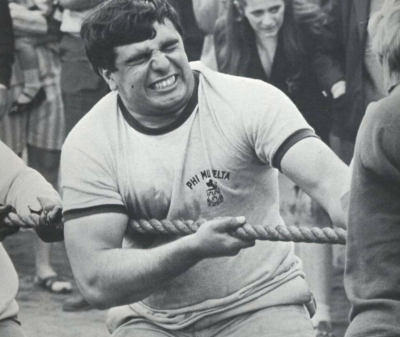

When Carrie Mae Weems photographed her students at Hampshire students circa 1990, she became aware of the differences in their interior lives. She asked them to first photograph somebody else before making a portrait of themselves, and noticed a difference in the way men and women presented themselves before the camera: “It’s sort of a vulnerability of revealing the self,” she said. 4 For the pictures of students in the gallery below, the observation holds true that student portraits exceed their connotations with mundane yearbook photography, and evade reductive conclusions about the position of their subject. The student portrait in fact reveals something beyond its initial generic implication, a way into the study of photography and its history from multiple perspectives.

1. Matthew S. Witkovsky. “Face Time.” In Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Da ner, and Maria Morris Hambourg, eds. Object:Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909–1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

2. See Ginger Hill’s treatment of the portraits of Frederick Douglass and his expression of political identity in “‘Rightly Viewed’: Theorizations of Self in Frederick Douglass’s Lectures on Pictures.” In Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, 41–82. Duke UP, 2012.

3. Hubertus von Amelunxen. “Afterword.” In Vilém Flusser: Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2000.

4. Carrie Mae Weems. The Lenny Interview: Carrie Mae Weems. Interview by Kimberly Drew, August 2016.