The female body in the West is not a unitary sign. Rather, like a coin, it has an obverse and a reverse: on the one side, it is white; on the other, not-white or, prototypically, black.1

–Lorraine O’Grady

Whenever someone deflects attention from my work to my identity as a CWA [Colored Woman Artist], I start to get nervous about whether they are actually seeing my work at all.2

–Adrian Piper

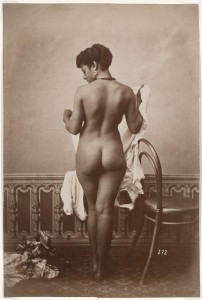

At some point during the decade of the 1870s, a young Woman of Color posed for the Italian photographer Gaudenzio Marconi in his studio. Marconi, an academy photographer who sold his photographic figure studies to budding young artists in desperate need of models, most likely chose for his model the exact pose that she holds in Academic nude study, from behind: standing, nude, head turned to the left, eyes demur and downcast. Marconi, in other words, posed his model in order to best accentuate the true subject of the photograph—the bare black body. In fact, we as viewers know nothing about this woman’s race or ethnicity, just as we know nothing of her thoughts, feelings or emotions; Marconi has stripped his model of everything but the state of her body—her objecthood. We gaze at and possess her, colonize her body with our spectatorship, and are unable to meet her eye.

Marconi’s photograph is just one of countless examples of what this exhibition refers to as the “colonizing gaze”: a way of looking that allows (often male, almost always white) Westerners to exoticize and objectify (most often female) “Easterners,” as well as people of color. The female body has thus been a site of hegemonic power struggles; these bodies are often used as both blank canvases onto which Westerners project their desires and as mirrors into which colonizers can gaze and see themselves. As African-American artist Lorraine O’Grady writes, “The female body in the West is not a unitary sign.” In her proclamation about the divisive nature of female bodies, bodies of color are too often used to throw white beauty into sharper relief, made clear by the cloth that Marconi’s model holds in front of her naked form. Or perhaps the bodies of women of color are simply seen as exotic objects, observed in all of their bizarre and fantastic detail—mined for fetishistic appeal and then discarded without ever really being seen. As O’Grady also remarks, “For at the end of every path we take, we find a body that is always already colonized.”3

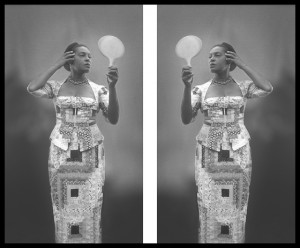

Contemporary female artists of color concerned primarily with their personal/political lives—artists like O’Grady—do not see “always already” inhabiting colonized bodies as a reason to submit to subjugation. Instead, artists represe nted here—women like Carrie Mae Weems and Mickalene Thomas, just to name a few—attempt to disrupt the viewer’s objectifying gaze and assert their agency by looking back. In a work like Weems’s photographic diptych, I looked and looked to See What so Terrified You (2003), the artist reasserts her agency not only in the declaration of her own subjecthood implied in the title—the looking “I”—but also in her literal refraction and reappropriation of the gaze. Instead of returning the colonizing gaze by looking back out onto the spectator, Weems turns the gaze onto herself through the use of hand-mirror and implies, in her confident posture and poise, that she could find nothing wrong or “terrifying” about her own image, thus denying the colonizing gaze of its oppressive force.

nted here—women like Carrie Mae Weems and Mickalene Thomas, just to name a few—attempt to disrupt the viewer’s objectifying gaze and assert their agency by looking back. In a work like Weems’s photographic diptych, I looked and looked to See What so Terrified You (2003), the artist reasserts her agency not only in the declaration of her own subjecthood implied in the title—the looking “I”—but also in her literal refraction and reappropriation of the gaze. Instead of returning the colonizing gaze by looking back out onto the spectator, Weems turns the gaze onto herself through the use of hand-mirror and implies, in her confident posture and poise, that she could find nothing wrong or “terrifying” about her own image, thus denying the colonizing gaze of its oppressive force.

Mickalene Thomas’s photography, like that of Weems, seeks to turn the models from objects back into subjects, to return them to themselves. Tamika sur une chaise longue (2008) follows the grand European tradition of th e reclining nude, focusing as it does on a partially naked woman who lies on her back and gazes directly at the viewer. Thomas here references one of the most famous reclining nudes in the Western canon—Manet’s Olympia from 1863—but, instead of relegating the black woman to the background as a simplistic stereotype, as in the older work, the artist places her front and center. The black female body is here transformed from an artistic archetype to a historical and personal specificity. Fellow contemporary African-American artist Kara Walker wrote that Thomas’s work “spirals inward,” in order to explore the identity and sexuality of her models.4 According to Walker, “A formerly exploitative gaze—Manet’s Olympia, Matisse’s odalisques—becomes the frame for a kind of post-womanist self-consciousness.”5

e reclining nude, focusing as it does on a partially naked woman who lies on her back and gazes directly at the viewer. Thomas here references one of the most famous reclining nudes in the Western canon—Manet’s Olympia from 1863—but, instead of relegating the black woman to the background as a simplistic stereotype, as in the older work, the artist places her front and center. The black female body is here transformed from an artistic archetype to a historical and personal specificity. Fellow contemporary African-American artist Kara Walker wrote that Thomas’s work “spirals inward,” in order to explore the identity and sexuality of her models.4 According to Walker, “A formerly exploitative gaze—Manet’s Olympia, Matisse’s odalisques—becomes the frame for a kind of post-womanist self-consciousness.”5

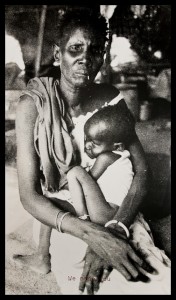

These works, both by African-American female artists, thus attempt to answer the call articulated by the feminist and race theorist bell hooks to move towards a “liberatory body politics,” one no longer defined by the violence and oppression of colonizing expectations.6 But the question of the Self and the Other haunts this exhibition, refusing to ever be completely ignored or dismissed out of hand. The Somali mother of Adrian Piper’s Ur-Mutter #2, too, acts as a ghost threading her way through the many strains of thought we examine here. “We Made You,” she claims, perhaps an accusation that accurately  comments on the relation between colonialist “subjects” and Othered “objects.” But the gaze of “our mother” is one of immense disappointment, one that perhaps extends beyond the confines of her persecuted body to remark on the inevitable frustrations of an exhibition like this. As Piper, a biracial and formerly black-identified artist, has herself noted, the category of “People of Color” can flatten difference between groups in a way that recapitulates the operating mechanisms of colonization.7 Is our exhibition, focused as it is on the “West” and the “Rest,” not in fact reiterating the very object-subject dynamic that these artists are attempting to refute? Perhaps the only answer to such a question—and the answer these artists themselves seem to provide—is that we are “always already” embedded into power dynamics that dictate our relationships with one another. Piper reflects that the content of the work itself should be prioritized over the identity of the artist, and while that may be ideal, it seems nearly impossible in a society dominated by notions of “us” and “them.” The solution this exhibition poses instead is to understand the political and personal motivations and messages behind each and every work of art, many of which attempt to break free of the constraints of colonialism. These artists, both “Others” and “Selves,” point the way to a future that does not rank human agency on a predetermined hierarchy. Instead of attempting to “make” them, perhaps we should follow the path they are paving and let them—the artists—make us.

comments on the relation between colonialist “subjects” and Othered “objects.” But the gaze of “our mother” is one of immense disappointment, one that perhaps extends beyond the confines of her persecuted body to remark on the inevitable frustrations of an exhibition like this. As Piper, a biracial and formerly black-identified artist, has herself noted, the category of “People of Color” can flatten difference between groups in a way that recapitulates the operating mechanisms of colonization.7 Is our exhibition, focused as it is on the “West” and the “Rest,” not in fact reiterating the very object-subject dynamic that these artists are attempting to refute? Perhaps the only answer to such a question—and the answer these artists themselves seem to provide—is that we are “always already” embedded into power dynamics that dictate our relationships with one another. Piper reflects that the content of the work itself should be prioritized over the identity of the artist, and while that may be ideal, it seems nearly impossible in a society dominated by notions of “us” and “them.” The solution this exhibition poses instead is to understand the political and personal motivations and messages behind each and every work of art, many of which attempt to break free of the constraints of colonialism. These artists, both “Others” and “Selves,” point the way to a future that does not rank human agency on a predetermined hierarchy. Instead of attempting to “make” them, perhaps we should follow the path they are paving and let them—the artists—make us.

—by Emma Jacobs

1 Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” in Art, Activism, and Oppositionality: Essays from Afterimage, ed. Grant H. Kester (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 268.

2 Adrian Piper, “The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artist,” in Out of Order, Out of Sight: Selected Writings, Vol. 2 (Cambridge: MIT, 1996), 166.

3 O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid,” 270.

4 Kara Walker, “Mickalene Thomas,” BOMB Magazine Spring 2009, <http://bombmagazine.org/article/3269/>.

5 Ibid.

6 bell hooks, “Naked Without Shame: A Counter-Hegemonic Body Politic,” in Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age, ed. Ella Shohat (Cambridge: MIT, 1998), 73.

7 Piper, “Triple Negation,” n.1, 161.